Odin

About

Overview

-

Open-source.

-

Created on (2016-07-07).

-

Overview .

-

FAQ .

-

Philosophy :

-

Simplicity and readability

-

Programs are about transforming data into other forms of data.

-

Data structures are just data.

-

Odin is not OOP.

-

Odin doesn't have any methods.

-

-

The entire language specification should be possible to be memorized by a mere mortal.

-

-

"The killer feature is that it has no features".

-

"bring them the 'joy of programming' back".

-

He ends the article by asking how to market the language, he doesn't know himself.

-

-

-

Paradigm :

-

Focus on the procedural paradigm.

-

GingerBill: "Odin is not a Functional Programming Language".

-

-

Roadmap :

-

FAQ:

-

There is no official roadmap. Public roadmaps are pretty much a form of marketing for the language rather than being anything useful for the development team. The development team does have internal goals, many of which are not viewable by the public, and problems are dealt with when and as necessary.

-

Odin as a language is pretty much done, but Odin the compiler, toolchain, and core library are still in development and always improved."

-

-

-

C Integration :

-

Odin was designed to facilitate integration with C code. It supports interfacing with C libraries directly and interoperability with other languages is facilitated.

-

-

Metaprogramming :

-

Odin offers some metaprogramming facilities, such as macros and templates, without becoming overly complex.

-

-

Compiler :

-

Written in C++.

-

-

Aimed systems :

-

Ginger Bill:

-

Odin has been designed specifically for modern systems: 32-bit and 64-bit platforms.

-

I highly recommend you don't use Odin, Zig or C for 8-bit chips; prefer a high-level assembly language instead.

-

-

-

Style :

-

We are not going to enforce any case style ever. You can do whatever you want.

-

Sources

-

-

Odin, RayLib.

-

Karl Zylinski on Odin and RayLib .

-

"Burnout with Unreal Engine".

-

No idea of what is happening in the engine.

-

Difficult and slow interaction.

-

C++.

-

etc.

-

-

"Odin fell into my lap and was perfect for what I wanted".

-

"Hot-reloading was the best thing I did; without it I would have gotten discouraged, because I am very impatient with iteration times".

-

Many things are in .dlls that are observed so if there are changes they reload, something like that.

-

"Don't necessarily create config files to tweak the game, but use code as data for tweaks".

-

Nah. Maybe if there is actual hot-reloading it can be okay, but a config file is very useful at times.

-

I think they are not mutually exclusive; config files are good for some things and hot-reloading for fast iterations.

-

-

-

"I made my own UIs, using Rectangles, with text inside, elegant borders, mouse hover system".

-

"I have fun and love the feeling of doing things from scratch".

-

"Why RayLib?"

-

"Reminder of how fun programming was in college when I was 22, now he's 36."

-

So, he didn't really answer the question.

-

-

Critiques of OOP, both from Karl and Wookash.

-

Nice.

-

Mentioned Mike Acton and DoD, etc.

-

-

Overall, the video is nice but doesn't talk about anything technical regarding Odin or RayLib.

-

-

-

-

Lives .

-

Odin, Zig, Haskell.

-

-

Nadako .

-

Sokol, SDL, Vulkan, all in Odin.

-

-

-

Odin, Zig.

-

Games and Apps made in Odin

My Impressions

Positives

-

Many! This has been my favorite language so far.

-

It's the most fun I had with a language!

-

Solves many problems I had with Zig, Rust, C/C++.

-

(2025-04-20) I really like the big focus on NAMES in the syntax :

-

I found the syntax very weird initially, but the reality is it is ultra intuitive and I have liked it a lot.

my_var := 123 my_proc :: proc() {}

-

-

(2025-04-20) No need for

;and don't miss it :-

I never missed

;, after all what made the experience positive are the{ }, not the;. -

You can use

;if you want, though.

-

-

(2025-04-20) No need for

( )in expressions :-

Much better than in Zig and C, nice.

-

-

(2025-04-20) Enum access is simple, similar to Swift :

-

Can be used as

.Ainstead ofMyEnum.A, in the correct context.

-

-

(2025-04-20) No need to specify return type for

voidwhen there is no return :-

Nice.

-

-

(2025-04-20) No methods :

-

Great.

-

-

(2025-04-20) Excellent built system :

-

Anything compared to C/C++ is excellent, to be fair.

-

Either way, it's by fair the easy language to compile I've seen.

-

-

(2025-04-20) The package system really seems very good, with folders :

-

Inspired by Go.

-

After seeing Ginger Bill's explanation in this video {26:50 -> 34:30} , I found it very nice.

-

Really seems to be a very good solution for managing exports/imports.

-

Negatives

-

(2025-12-12) I don't like the

contextsystem at all .-

I have lots of critiques around it.

-

See Context .

-

I had a discussion about this topic in this discord thread .

-

There's also other topics about explicitness that I'd like to go through, but I think what I wrote sums it up what I bothered me today.

-

-

(2025-12-13) I don't like

@(init)and@(fini).-

Quoting a snippet from the discord thread about that I found interesting and agree with:

-

Barinzaya:

-

I think

@(init)procs are kind of an anti-pattern. I dislike the "this proc is now always going to be called whether you want it or not" nature of it.

-

-

Caio:

-

I completely agree. The only reason I used

@(init)in this situation, was because other libraries do. I had to place the profiler earlier than all of them, so the only way to do it is by also being@(init)or going before than_startup_runtime.

-

-

-

(2025-11-13) I don't like how

@(require_results)is NOT the default way of handling results; I would prefer the opposite .-

By default, errors can be ignored. Not good. Things like

#optional_okand#optional_allocator_errorexists, but the main problem is actually how@(require_results)is optional. By the default a procedure will not require the results to be handled. I wish the opposite was true: you have to opt out of required results and use something like@(optional_results); the priorities should have been inverted. -

There's also the annoyance of having to add

@(require_results)for every math function and similar, etc. -

I made a suggestion for something like

#+vet explicit-returns, as way to have every unhandled return be treated as an error, even for#optional_okor#optional_allocator_error, as well as a compiler flag. This would just be an optional flag, per file (even tho I prefer per library), but it was denied :/

-

-

(2025-11-13) I don't like the implicit usage of

context.allocatoraround A LOT of libraries, basically being the standard in Odin .-

This has led me to more bugs that it has helped anything.

-

Also, this leads to code that focuses heavily on "constructors" and "destructors", as by default the

context.allocatoris aruntime.heap_allocator(), which is just a wrap aroundmalloc.-

Some libraries are ok with you using an arena in its place, but other libraries use

defer delete()implicitly and that makes it incompatible with a more straight forward and optimized design of managing memory, focused on lifetimes with arenas.

-

-

Currently, to improve this:

-

I use

panic_allocatoras the default forcontext.allocator, by using the-default-to-panic-allocatorflag. I don't ever reassign thecontext.allocator. I use it as thepanic_allocatorduring all the application, so if I forget to be explicit about an allocation, the app crashes. This is far from perfect, as this is a runtime check, but it's better than losing track of your memory. -

I use

#+vet explicit-allocatorson top of every file. This make it soallocator := context.allocatorgives an error. Sonew(int)will give an error, butnew(int, allocator)will not. Also not perfect, as I'd prefer this to be a compilation flag, etc.

-

-

Both improvements above just hides the problem a bit. I don't like how I had to go around one of the main language design just so I have safer and sane code.

-

Even if

contextwas removed, code could go fromallocator := context.allocatortoallocator := runtime.allocator(thread local global variable, as I suggested). So it's not much of acontextthing, but more about how the language heavily favors design of default allocators, and implicitness. -

I can think of this either being solved by removing default parameters in procedures, or having a code style that enforces explicit allocators instead of the opposite.

-

-

(2025-11-13) I would prefer if there was no default parameters in procedures .

-

This sounds a bit wild, but I came to realize how little I actually need default parameters.

-

They result in implicit behavior, which I believe leads to worse code.

-

Meanwhile, working without default parameters is actually an interesting challenge to solve that I think results in much better APIs.

-

-

(2025-04-20) I don't like

usingoutside of structs :-

Ginger Bill also considers this a mistake.

-

Read the

usingsection for more information.

-

-

(2025-04-20)

Lack of keywords for concurrency is somewhat annoying (async/await) .-

Maybe this is ok, but I do have to investigate a bit more about this.

-

(2025-11-13)

-

Well, I made a library for that, so problem solved. I much rather having my library then using something built in the language now, I think.

-

-

-

(2025-04-20)

Down-casting can be complex :-

I cannot compare subtypes, like in GDScript, with

is:

func _detect_hitbox(area: Area2D) -> void: if not (area is Hitbox): Debug.red('(%s | Hurtbox) The area is not a Hitbox.' % _name) return-

It is necessary to use advanced idioms, with Unions / Enums, etc., to get the desired information.

-

See Odin#Advanced Idioms, Down-Cast and Up-Cast for more information.

-

(2025-11-13)

-

I think I'm ok with this. It's actually really rare I have to use something like the code shown in GDScript, and avoiding these situations led the code to be more understandable.

-

It's a lower level thing, but once you get used to it, I think it's ok.

-

-

-

(2025-04-20)

Having to use:->for function return-

Minor, but I feel it could be hidden.

-

(2025-07-03)

-

Genuinely, I don't care at all.

-

-

-

(2025-04-20)

Having to use:casekeyword for switches-

Minor, but I think the keyword shouldn't exist.

-

(2025-07-03)

-

Genuinely, I don't care at all.

-

I actually kind of like it.

-

-

-

(2025-04-20)

Having to use:prockeyword for procedures-

Ultra minor, I got used to the keyword and it's convenient when considering how similar the syntax is to:

my_proc :: proc() {} my_struct :: struct {} -

(2025-07-03)

-

JAI opts not to use the keyword, but I have come to appreciate its use.

-

-

Installation

Versions used

-

(2025-12-05)

-

Odin: I'm using

dev-2025-12(2025-12-04).cd C:\odin .\build.bat release -

OLS: I'm using

787544c1(2025-12-03).cd C:\odin-ols .\build.bat-

Remember to stop all OLS executions in VSCode, or just close VSCode.

-

Building from source

-

Repo .

-

x64 Native Tools Command Prompt for VS 2022-

Search for this terminal in the Windows search bar.

-

-

cd c:\odin -

build.bat-

or

build.bat releasefor a faster compiler (the command takes longer).

-

-

build_vendor.bat. -

Considerations :

-

Apps running Odin must be closed.

-

VSCode can stay open, but .exe compiled with Odin must be closed.

-

-

Building

Build

-

Compiles, generates executable.

odin build .

Run

-

Compile, generate executable, run executable.

odin run . -

.refers to the directory. -

Odin thinks in terms of directory-based packages. The

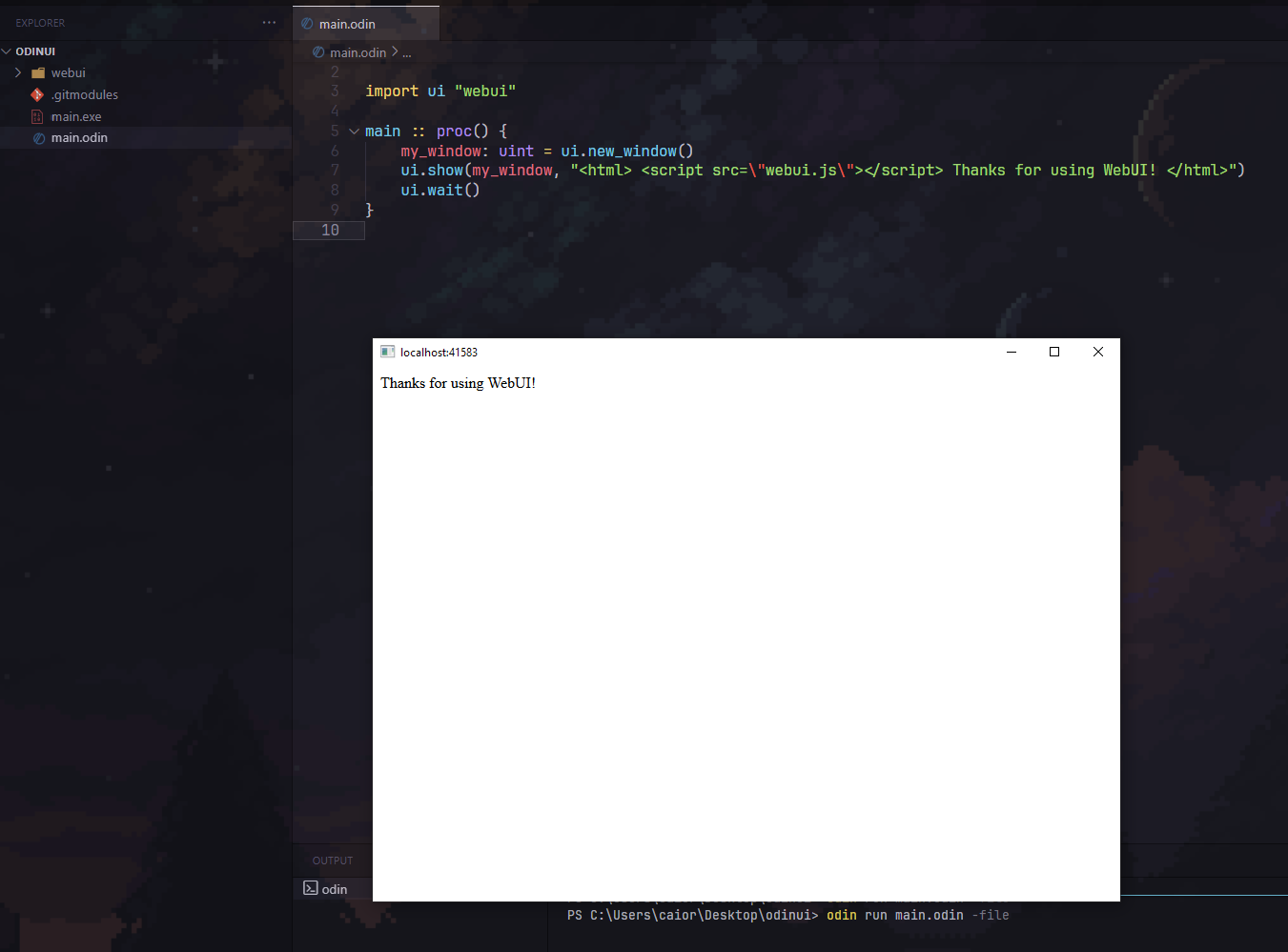

odin build <dir>command takes all the files in the directory<dir>, compiles them into a package and then turns that into an executable. You can also tell it to treat a single file as a complete package by adding-file, like so:odin run hellope.odin -file

Help

-

odin build -help -

Output path:

-

odin build . -out:foo.exe -

odin build . -out:out/odin-engine.exe-

The directory is not created by default, so if the

outdir doesn't exist it will give an error in the build; usemkdirbeforehand.

-

-

Subsystems

Remove terminal from executable

-

For Windows:

-

-subsystem:windows.

-

Compile-time Stuff

Compile-time Flags

-

Check

base:builtin/builtin.odin.

When

-

when. -

Certain compile-time expressions.

-

The

whenstatement is almost identical to theifstatement but with some differences:-

Each condition must be a constant expression as a

whenstatement is evaluated at compile time . -

The statements within a branch do not create a new scope.

-

The compiler checks the semantics and code only for statements that belong to the first condition that is

true. -

An initial statement is not allowed in a

whenstatement. -

whenstatements are allowed at file scope.

-

when ODIN_ARCH == .i386 {

fmt.println("32 bit")

} else when ODIN_ARCH == .amd64 {

fmt.println("64 bit")

} else {

fmt.println("Unsupported architecture")

}

#config

In Code

-

TRACY_IS_ENABLED :: #config(TRACY_ENABLE, false)-

The name on the left is for code use. The name on the right is for the compiler.

-

They can be the same, it doesn't matter.

-

Compilation Flag

odin run . -define:TRACY_ENABLE=true

-

Caio:

-

If a lib defines

OPTION :: #config(OPTION, false), is it possible for me to enable it in my app, without using compiler flags? If I redefine it in my app asOPTION:: #config(OPTION, true), it doesn't work.

-

-

Oskar:

-

Only compiler flag.

-

Procedure Disabled

@(disabled=CONDITION)

-

Disabled the procedure at compile-time if the condition is met.

-

The procedure will not be used when called.

-

The procedure cannot have a return value.

-

The procedures using this are still type-checked.

-

This differs from Zig. Odin tries to check as much as possible.

-

-

Modify the compilation details or behavior of declarations.

Static / Read-Only

-

@(static)

Read-only

-

@(rodata)

Comp-time Loop

-

Barinzaya:

-

There's no compile-time loop, though. I seem to recall Bill saying something about not wanting to add it, IIRC because it's a bit of a slippery slope (e.g. then people will want to be able to iterate over struct fields). I can't find the message I'm thinking of, though.

-

-

Sobex:

-

Since you unroll you can kinda do a unrolled loop with inlined recursion

-

comp_loop :: #force_inline proc(as: []int, $i: int, $end: int) {

_, _ = args[i].(intrinsics.type_proc_parameter_type(F, i))

a := as[i]

fmt.print(a)

when i + 1 != end do comp_loop(as, i+1, end)

}

as := [?]int{5, 4, 3, 2, 1}

comp_loop(as[:], 0, 5)

```

Build Tags

-

Used to define build platforms.

-

It is recommended to use File Suffixes anyway.

-

This has a function, not just decorative.

-

"For example,

foobar_windows.odinwould only be compiled on Windows,foobar_linux.odinonly on Linux, andfoobar_windows_amd64.odinonly on Windows AMD64."

-

Ignore

#+build ignore

Optimizations

Force Inline (

#force_inline

)

-

Doesn't work on

-o:none.

Intrinsics

-

intrinsics.type_is_integer()-

Caio:

proc (a: [$T]any) where intrinsics.type_is_integer(T) Expected a type for 'type_is_integer', got 'T' intrinsics.type_is_integer(T) -

Blob:

-

Because the type of

Tis an untyped integer, as it's technically a constant, & there's no way to check against an untyped type (I would like there to be honestly). What you'd want to check against is the type of the array itselfproc (a: $E/[$T]any) where intrinsics.type_is_array(E).

-

-

-

intrinsics.type_elem_type()-

Underlying type.

-

Useful for arrays.

-

Custom Attributes

-custom-attribute:<string>

Add a custom attribute which will be ignored if it is unknown.

This can be used with metaprogramming tools.

Examples:

-custom-attribute:my_tag

-custom-attribute:my_tag,the_other_thing

-custom-attribute:my_tag -custom-attribute:the_other_thing

-

If you don't use this flag for a custom attribute, there will be a compiler error.

-

I imagine this is best used when in conjunction with

core:odin/parser, or something like it?

Example

@(my_custom_attribute)

My_Struct :: struct {

}

Package System

What is a Package

-

"A Package is basically a folder with Odin code in it, where everything inside that folder becomes part of that package".

-

"The Package system is made for library creation, not necessarily to organize code within a library".

-

-

Examples show how using different packages within the same game can create friction, as:

-

You have to be careful with cyclic dependencies.

-

You have to use imported library name prefixes everywhere.

-

-

-

Everything is accessible within the same Package.

-

"The only reason to separate code into different files within the same package is for code organization; in practice it's as if everything were together".

-

In the given example, all files can communicate with each other without "include", since all belong to the same package and will be compiled into a single "thing".

-

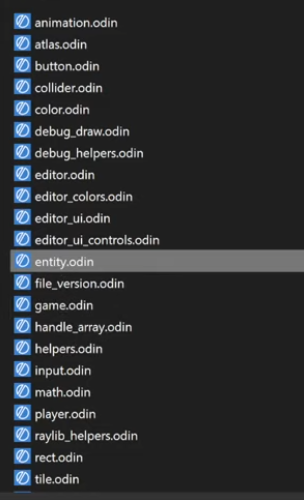

.

.

-

"I can simply cut the code and paste it in another file and everything will still work the same".

-

Basic Usage

Creating a package

-

"Packages cannot have cyclic references".

-

"game -> ren".

-

"ren -!> game".

-

-

Keyword

package:-

All files must have a

packageat the top.-

The name does not need to be the same as the folder the file is in, it can be anything.

-

-

All files within the same package must have the same name at the top.

-

If not, it gives a compiler error.

-

-

Which name to use :

-

If you are making a game, the

packagename is not very important. -

But if you are making something intended for use by others, then choose a good and unique name among existing package names.

-

-

Installing a new package

-

Download the folder, put it there, it works.

Using a package

-

From a collection :

import rl "vendor:RayLib" -

From the file system :

-

If no prefix is present, the import will look relative to the current file.

import ren "renderer" // Uses the "renderer" package (folder).import cmn "../common" // goes to the parent package (parent folder) and gets the "common" package (folder). -

Collections

-

Odin has the concept of

collectionsthat are predefined paths that can be used in imports. -

core:The most common collection that contains useful libraries from Odin core likefmtorstrings.

Standard Collections

-

Base :

-

Core :

-

Useful and important things, but not fundamental.

-

-

Vendor :

-

3rd party, but included with Odin.

-

"High-quality, officially supported".

-

-

Joren:

-

When the spec is written (around v1's release), it will be clarified that there are 3 standard "collections":

-

base: defined by the language specification, expected to work the same no matter the compiler vendor,

-

core: would be nice if it mirrors upstream Odin's packages for interoperability, but up to the compiler vendor,

-

vendor: things like RayLib, DirectX, entirely up to the compiler vendor what's shipped here,

-

-

You can still opt to fork Odin and tweak things in

base, but at that point you have your own dialect of the language that can no longer necessarily be compiler by another Odin implementation, even if you copy acrosscore.

-

Shared Collection

-

There's a

sharedfolder in the Odin installation folder that you can use for that. It's available as a collection by default (e.g.import "shared:some_package")

Creating new Collections

-

You can define your own collection at build time .

-

You can specify your own collections by including

-collection:name=some/pathwhen running the compiler. -

There's no built-in way to make it "permanent" though.

-

The following will define the collection

projectand put the path at the current directory. -

In the project :

import "my_collection:package_a/package_b"

-

While building :

odin run . -collection:my_collection=<path to "my_collection" folder>

-

If you are using

my_collectionin code, but you forget to specify the build flag, then the project will simply not compile, as Odin doesn't know where "my_collection" is.

Declaration Access

-

All declarations in a package are public by default.

-

@(private="package")/@(private)-

The declaration is private to this package.

-

Using

#+privatebefore the package declaration will automatically add@(private)to everything in that file.

-

-

@(private="file")-

The declaration is private to this file.

-

#+private fileis equivalent to automatically adding@(private="file")to each declaration.

-

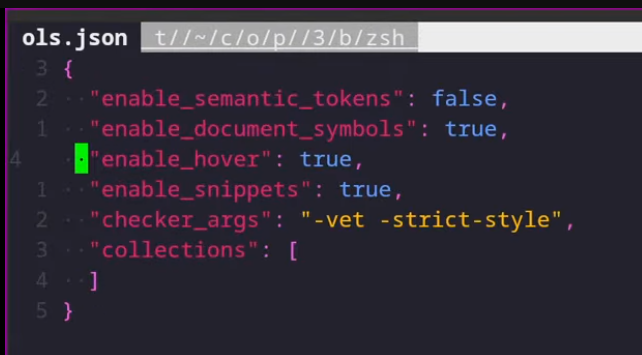

LSP (OLS - Odin Language Server)

-

OLS .

-

I downloaded OLS, used

build.batandodinfmt.bat. -

Stored the entire OLS folder in a directory.

-

Installed the VSCode extension.

-

Set the path of

ols.exein Odin settings inside VSCode. -

Created the

ols.jsonfile in my project directory in VSCode, with configs from the OLS GitHub.

Check Args

-

odin check -help

Examples

-

Rickard Andersson's OLS

-

.

.

Operations

Arithmetic Operations

%

-

Modulo (truncated).

-

%is dividend

%%

-

Remainder (floored).

-

%%is divisor. -

For unsigned integers,

%and%%are identical, but the difference comes when using signed integers.

Logical Operations

"Short-Circuit"

-

It means that if the first condition is

falsethen the second condition won't be evaluated. -

This works for any control flow, as the "short-circuiting" is a property of the logical operators (

&&,||), not the control flow.-

So this is also applicable to ternary operations, for example.

-

-

if a != nil && a.something == true {}-

This is safe, as when the first condition is

false, the second one will not be evaluated.

-

-

if a.something == true && a != nil {}-

This is unsafe. The first condition will be evaluated first, so if

a == nil, this will crash.

-

conditional AND (

&&

)

a && b is "b if a else false"

conditional OR (

||

)

a || b is "true if a else b"

Bitwise Operations

OR (

|

)

-

.

XOR (

~

)

-

~u32(0)is effectivelymax(u32).

AND (

&

)

-

.

AND-NOT (

&~

)

-

.

LEFT SHIFT (

<<

)

-

.

RIGHT SHIFT (

>>

)

-

.

Control Flow (if, when, switch, for, defer)

If

-

If .

if x >= 0 {

fmt.println("x is positive")

}

-

Initial statement :

-

Like

for, theifstatement can start with an initial statement to execute before the condition. -

Variables declared by the initial statement are only in the scope of that

ifstatement, including theelseblocks.

if x := foo(); x < 0 { fmt.println("x is negative") }if x := foo(); x < 0 { fmt.println("x is negative") } else if x == 0 { fmt.println("x is zero") } else { fmt.println("x is positive") } -

If Ternary

bar := 1 if condition else 42

// or

bar := condition ? 1 : 42

For

-

For .

-

It's the only type of loop.

-

Braces

{ }or adoare always required.

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

fmt.println(i);

}

for i := 0; i < 10; i += 1 { }

for i := 0; i < 10; i += 1 do single_statement()

for i in 0..<10 {

fmt.println(i)

}

// or

for i in 0..=9 {

fmt.println(i)

}

str: string = "Some text"

for character in str {

assert(type_of(character) == rune)

fmt.println(character)

}

memory_block_found := false

for block := arena.curr_block; block != nil; block = block.prev {

if block == temp.block {

memory_block_found = true

break

}

}

Switch

-

switchis runtime. The compiler doesn't know if those cases are actually reachable or not, so it needs to check them all.-

The switch evaluates the possibility of entering each case, so the operation inside each case must be compatible.

-

-

The Switch has no fallthrough, but requires the use of the

casekeyword.

switch arch := ODIN_ARCH; arch {

case .i386, .wasm32, .arm32:

fmt.println("32 bit")

case .amd64, .wasm64p32, .arm64, .riscv64:

fmt.println("64 bit")

case .Unknown:

fmt.println("Unknown architecture")

}

Partial

Foo :: enum {

A,

B,

C,

D,

}

f := Foo.A

switch f {

case .A: fmt.println("A")

case .B: fmt.println("B")

case .C: fmt.println("C")

case .D: fmt.println("D")

case: fmt.println("?")

}

#partial switch f {

case .A: fmt.println("A")

case .D: fmt.println("D")

}

Type switch

-

vis the unwrapped value fromvalue.

value: Value = ...

switch v in value {

case string:

#assert(type_of(v) == string)

case bool:

#assert(type_of(v) == bool)

case i32, f32:

// This case allows for multiple types, therefore we cannot know which type to use

// `v` remains the original union value

#assert(type_of(v) == Value)

case:

// Default case

// In this case, it is `nil`

}

-

Note :

-

Having multiple types in a single case will mean it won't be unwrapped, as there's no one type the complier can guarantee it'll be.

-

Defer

-

Defer .

-

A defer statement defers the execution of a statement until the end of the scope it is in.

-

The following will print

4then234.

package main

import "core:fmt"

main :: proc() {

x := 123

defer fmt.println(x)

{

defer x = 4

x = 2

}

fmt.println(x)

x = 234

}

Procedures

-

Procedure used to be the common term as opposed to a function or subroutine. A function is a mathematical entity that has no side effects. A subroutine is something that has side effects but does not return anything.

-

A procedure is a superset of functions and subroutines. A procedure may or may not return something. A procedure may or may not have side effects.

multiply :: proc(x: int, y: int) -> int {

return x * y

}

fmt.println(multiply(137, 432))

multiply :: proc(x, y: int) -> int {

return x * y

}

fmt.println(multiply(137, 432))

-

Everything in Odin is passed by value, rather than by reference.

-

All procedure parameters in Odin are immutable values.

-

Passing a pointer value makes a copy of the pointer, not the data it points to.

-

Slices, dynamic arrays, and maps behave like pointers in this case (Internally they are structures that contain values, which include pointers, and the “structure” is passed by value).

Calling Conventions

-

Procedure types are only compatible with the procedures that have the same calling convention and parameter types.

odin

-

By default, Odin procedures use the

"odin"calling convention. -

This calling convention is the same as C, however it differs in a couple of ways:

-

It promotes values to a pointer if that’s more efficient on the target system

-

Where would this be more efficient?

-

It passes all parameters larger than

16 bytesby reference. -

The promotion is enabled by the fact that all parameters are immutable in Odin, and its rules are consistent for a given type and platform and can be relied on since they are part of the calling convention.

-

Passing a pointer value makes a copy of the pointer, not the data it points to. Slices, dynamic arrays, and maps have no special considerations here; they are normal structures with pointer fields, and are passed as such. Their elements will not be copied.

-

Note: This is subject to change.

-

-

It includes a pointer to the current context as an implicit additional argument .

-

contextless

-

Same as

odinbut without the implicitcontextpointer.

stdcall / std

-

This is the

stdcallconvention as specified by Microsoft.

c / cdecl

-

This is the default calling convention generated of a procedure in C.

-

If it's within a

foreignblock, the default calling conventions iscdecl.

fastcall / fast

-

This is a compiler dependent calling convention.

none

-

This is a compiler dependent calling convention which will do nothing to parameters.

Variadic Arguments

-

Ginger Bill: "It's just a slice allocated on the stack."

foo :: proc(x: ..int) {} // Calling foo(1, 2, 3) // is the same as temp_array := [3]int{1, 2, 3} temp_slice := temp_array[:] foo(..temp_slice) -

Procedures can be variadic, taking a varying number of arguments:

sum :: proc(nums: ..int) -> (result: int) {

for n in nums {

result += n

}

return

}

fmt.println(sum()) // 0

fmt.println(sum(1, 2)) // 3

fmt.println(sum(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)) // 15

odds := []int{1, 3, 5}

fmt.println(sum(..odds)) // 9, passing a slice as varargs

Multiple returns

swap :: proc(x, y: int) -> (int, int) {

return y, x

}

a, b := swap(1, 2)

fmt.println(a, b) // 2 1

-

Implicitly :

end_msg_as_bytes, err_end := cbor.marshal_into_bytes(end_msg) -

Explicitly :

end_msg_as_bytes: []byte err_end: cbor.MarshalError end_msg_as_bytes, err_end = cbor.marshal_into_bytes(end_msg) // or packet_as_bytes: []byte; err_packet: cbor.Marshal_Error

packet_as_bytes, err_packet = cbor.marshal_into_bytes(packet[:])

```

Closures (They don't exist)

-

Does not have closures, only Lambdas.

-

Odin only has non-capturing lambda procedures.

-

For closures to work correctly would require a form of automatic memory management which will never be implemented into Odin.

foo :: proc() {

y: int

x := proc() -> int {

// `y` is not available in this scope as it is in a different stack frame

return 123

}

}

Procedure Groups (explicit overload)

-

Caio:

-

if I have a struct that inherits another struct with

using, and then I make a procedure group, where the first procedure accepts the original struct, and the second accepts the struct that inherits the first struct, what would happen? This "higher level" struct would call which of these procedures? Does it depend on the order the procedures are stored in the procedure group, or something like that? Casting has been the weirdest thing for me.

-

-

Barinzaya:

-

The order of the procs in the proc group isn't used to decide which to call, the compiler "scores" each candidate to decide which one is the best fit for a given call. As best I can tell it does appear that the compiler accounts for subtypes when doing this, so it should consistently call the proc closest to the base type https://github.com/odin-lang/Odin/blob/090cac62f9cc30f759cba086298b4bdb8c7c62b3/src/check_expr.cpp#L829.

-

-

Odin:

-

In retrospect it sounds a bit weird that odin checks for subtyping in cases of proc groups, but it can't be done directly. In a way, overloading itself sounds weird with no RTTI. Is it just because of the c++ part of odin? We were talking about options for downcasting, but maybe a proc group could also be an option while not having to store any extra data in the struct? I have no idea, it just sounds odd going back to proc groups after the limitations we were talking about. I wonder what would be cheaper, letting a proc group handle the polymorphism, or using a union subtype polymorphism as discussed

-

-

Jesse:

-

Nothing to do with the language choice for the compiler.

-

It's a compile time switch basically. A better designed

_Genericmacro from C. -

They act on type information available at compile time. There's nothing runtime about proc groups.

-

Generics

-

Use of

$Tin parameter type of the procedure. -

Fun facts :

-

Parapoly doesn't support default values.

-

[]$MEMBERcan't have a default value, for example.

-

-

-

Specialization :

array: $T/[dynamic]$E-

T:-

Type of the entire array.

-

-

E:-

Type of the element inside the array.

-

-

Force parameters to be compile-time constants

-

Use of

$Tin parameter name of the procedure.

my_new :: proc($T: typeid) -> ^T {

return (^T)(alloc(size_of(T), align_of(T)))

}

ptr := my_new(int)

Deferred

-

@(deferred_in=<proc>)-

will receive the same parameters as the called proc

-

-

@(deferred_out=<proc>)-

will receive the result of the called proc.

-

-

@(deferred_in_out=<proc>)-

will receive both

-

-

@(deferred_none=<proc>)-

will receive no parameters.

-

Return from a deferred procedure

-

what happens if I have a

@(deferred_none=end) begin :: proc() -> booland aend :: proc() -> bool, and I callresult := begin()? How does the return of deferred procedures work? Wouldresulthold the value ofbeginor something else?-

resultwill hold the return value frombegin, the return value ofendwill be silently dropped when it runs -

It'd be equivalent to

result := begin() defer end() -

Typing

Declaration

Constants

u :: "what";

// Untyped.

y : int : 123

// Explicitly typed constant.

-

::is closer to#definethan it isstatic const. -

To achieve similar behaviour to C’s

static const, apply the@(rodata)attribute to a variable declaration (:=) to state that the data must live in the read-only data section of the executable. -

"Anything declared with

::behaves like a constant. That includes types and procs." -

Aliases :

Vector3 :: [3]f32

Variables

x: int

// default to 0

// All below are equivalent.

x : int = 123

x : = 123

x := 123

x := int(123)

-

Multi-declaration :

y, z: int

// both are int.

Literal Types

-

Literals are

untyped, butuntypedvalues doesn't have to be from a literal; you can getuntypedvalues from builtins likelenwhen applicable. -

"I might say that a literal rune is a piece of syntax that yields an untyped rune".

-

untypedusually means it comes from a literal, though sometimes intrinsics/builtins can give them too. -

It basically just means a compile-time-known value.

-

rgats:

-

i can see why some people prefer literals having static types,

10is always an int in C -

and the conversions happen at runtime

-

but i dont think it makes a very big difference in most cases

-

honestly i think it'd make a bigger difference in a language without type inference

-

in C you have to specify the type of your literal,

10,10u,10f,10l, etc, and you also have to specify the type of your variable, likeunsigned long long x = 10ull; -

c implicitly converts

inttounsigned long longi believe, but if you actually wanted a very large number you'd need to specify the type (edited)Monday, 27 October 2025 15:31 -

so it gets extra messy there

-

and not every number converts implicitly, i dont think

float x = 10.5;works for example, which gets annoying

-

Untyped Types

-

Can be assigned to constants (

::) without being forced into a specific type, but once it gets assigned to a variable (=) it has to have an actual type.

A_CONSTANT :: 'x'

// is an untyped thing you can make yourself

Zero Value

-

Variables declared without an explicit initial value are given their zero value.

-

The zero value is:

-

0for numeric and rune types -

falsefor boolean types -

""(the empty string) for strings -

nilfor pointer, typeid, and any types.

-

-

The expression

{}can be used for all types to act as a zero type.-

This is not recommended as it is not clear and if a type has a specific zero value shown above, please prefer that.

-

Broadcasting

Directive

-

#no_broadcast

Example

-

Caio:

-

I have this procedure:

tween_create :: proc( value: ^$T, #no_broadcast end: T, duration_s: f64, ease: ease.Ease = .Linear, start_delay_s: f64 = 0, custom_data: rawptr = nil, on_start: proc(tween: ^Tween) = nil, on_update: proc(tween: ^Tween) = nil, on_end: proc(tween: ^Tween) = nil, loc := #caller_location ) -> (handle: Tween_Handle) { //etc }-

And I call it with:

tween_create( value = &personagem_user.arm1.pos_world, end = arm_relative_target_trans.pos, duration_s = 0.1, on_end = proc(tween: ^eng.Tween) { personagem_user.arm1.is_stepping = false }, )-

So why don't I get a compile error, considering that

valueis a[2]f32andendis af32?

-

-

Thag and Blob:

-

Because

f32can broadcast to[2]f32

my_arr: [2]f32 my_arr = 3.0 fmt.println(my_arr) // [2]f32{3.0, 3.0}-

it's really useful in certain cases

-

like allowing you to do:

my_vec *= 2-

you can add

#no_broadcast paramto procs params to stop it doing so. -

in front of the param

#no_broadcast end: T-

you can add it both to

valueandendif you want.

-

Casting

-

All the syntaxes below produce the exact same result.

-

Those are semantic casts. It's a compiler-known conversion between two types in a way that semantically makes sense.

-

A straightforward example would be converting between

intandf64; the conversion will have the same numerical value, which will change its representation in memory.

i := 123

f := f64(i)

u := u32(f)

i := 123

f := (f64)(i)

u := (u32)(f)

i := 123

f := cast(f64)i

u := cast(u32)f

~Auto Cast Operator

-

The

auto_castoperator automatically casts an expression to the destination’s type if possible. -

This operation is only recommended for prototyping and quick tests. Do not overuse it.

x: f32 = 123

y: int = auto_cast x

Advanced Idioms, Down-Cast and Up-Cast

-

Subtyping in procedure overload :

-

Area to Hurtbox and Hurtbox to Area :

-

Very useful.

-

Caio:

-

Consider an

Areaand aHurtboxtype, whereHurtboxinherits fromArea(using area: Area).

obj := Area{ area_entered = some_func_pointer, area_exited = some_func_pointer, } fmt.printfln("OPERATION 1: %v", cast(Hurtbox)obj) fmt.printfln("OPERATION 2: %v", cast(^Hurtbox)&obj)-

The Operation 1 is not allowed, and the Operation 2 causes a Stack-Buffer-Overflow. My question is: how / why does this happen, for both operations?

-

-

Barinzaya:

-

A

Hurtboxis anAreaplus more (theAreais just part of theHurtbox). When you assignobjto be anArea, it is only the contents of anArea, there's no extra space reserved for the extra things that aHurtboxwould also contain. -

Subtyping can easily downcast (

HurtboxtoArea) because everyHurtboxcontains a completeArea, but upcasting (AreatoHurtbox) only works on an^Areathat points into a completeHurtbox.-

NOTE : You can only cast if it's also the first field, otherwise you'd need to use

container_of. -

When you make a variable of type

Area, it isn't part of a completeHurtbox

-

-

Odin doesn't implicitly embed any RTTI (Runtime Type Information) in the type, so you can't definitively tell whether a given

Areais part of aHurtboxor not, so there is nodynamic_cast/type-aware pointer casting. -

That's where patterns like

union-based subtype polymorphism come into play--that's an approach to adding that extra information for you to know what type it is.-

Though it stores a self-pointer, so it can cause issues if you later copy the struct without updating it.

-

-

-

Caio:

-

Isn't there a way to do something like gdscript does:

if not (area is Hitbox): return, for example? -

I mean, can I check for something like the length of the object inside the pointer, to see if the length corresponds to a complete Area or something more? I'm not sure if my question makes sense, as I don't know if checking for the content of the ^Area would give me something besides what an Area has

-

-

Barinzaya:

-

That would require Odin to implicitly add extra info into the

struct. It doesn't do that. -

And as for the length: That info isn't in the type. If you're talking like

size_of(ptr^)or something, the compiler is just going to give you that info based on what it knows based on the types. It doesn't do any kind of run-time lookup to try to figure it out. -

"as I don't know if checking for the content of the ^Area would give me something besides what an Area has". That's exactly what I'm saying--there is no other info there other than what you put in the

struct. There's nothing to check, unless you put it there yourself. -

Subtyping is syntax sugar, and nothing more.

-

-

Caio:

-

So my only options are:

-

Place some more info in the struct to avoid casting blindly

-

Yolo cast blindly, but only do the casting if you are sure it's safe (like I'm doing for the function pointers inside the structs).

-

-

-

Barinzaya:

-

Basically, yes.

-

Number 1 is what OOP languages do, they just do it implicitly. Odin doesn't do that.

-

More specifically: that info has to come from somewhere . If all you have is an

^Area, then it has to come from inside of thestruct, but it could also come from something associated with the pointer. -

A

unionof pointers or anany, they store both a pointer and a tag/typeidrespectively that they use to know what the pointer actually points it.-

He means in the sense of not receiving

^Arenadirectly, but anunionoranyin its place

-

-

-

Transmute

-

It is a bitcast; that is, it reinterprets the memory for a variable without changing its actual bytes.

-

Using the same example as above,

transmuteing frominttof64will keep the same representation in memory, which means the numerical value will be different. -

This can be useful for bit-twiddling things in floats, for instance;

core:mathdoes that for some of its procs.

f: f32 = 123

u := transmute(u32)f

Type Conversions

From

int

to

[8]byte

-

transmute([8]byte)i -

A fixed array is its data, so transmuting will give you the actual bytes of the

int. -

You may also want to consider casting to one of the endian-specific integer types first if you care about the bytes being the same on big-endian systems.

From

[]int

to

[]byte

-

[]intss a slice, buttransmuteing tou8won't change the length; a slice of 4ints wouldtransmuteinto a slice of 4u8s. -

You probably want to use

slice.to_bytes(or more generically,slice.reinterpret). That will give you au8slice with the correct size. -

The same note about endianness applies here, but it's not as straightforward to convert between the two.

From

[]T

to

[]byte

-

transmute([]byte)my_slice-

Doesn't work well.

-

"It will literally reinterpret the slice itself as a byte slice; you have to use something in

core:sliceorencoding".

-

From

string

to

cstring

-

strings.unsafe_string_to_cstring(st)-

Action : Alias.

-

The internal operation is:

raw_string := transmute(mem.Raw_String)s cs := cstring(raw_string.data)

-

-

strings.clone_to_cstring(s)-

Action : Copy.

-

From

string

to

rune

-

for in-

Assumes the string is encoded as UTF-8.

s := "important words" for r in s { // r is type `rune`. // works equally for any UTF-8 char; e.g., Japanese, etc. }-

Action : Stream

-

From

string

to

[]rune

-

utf8.string_to_runes(st)-

Action : Copy

-

From

string

to

byte

last_character := s[len(s) - 1]

// This is a `byte` / `u8`

// string length is in bytes

for idx in 0..<len(s) {

fmt.println(idx, s[idx])

// 0 65

// 1 66

// 2 67

}

From

string

to

[]byte

-

transmute([]byte)s-

Action : Alias.

-

Is functionally a

[]bytewith different semantics, so you can transmute to it. -

This works because their in-memory layout is the same; see

runtime.Raw_Sliceandruntime.Raw_String. -

Does not work for

untyped string.-

The type needs to be explicit.

// Does not work msg :: "hello" data := transmute([]u8)msg // Works msg: string : "hello" data := transmute([]u8)msg -

-

From

string

to

[^]byte

-

raw_data(s)-

Action : Alias.

-

From

[]string

to

[]byte

-

It's effectively a pointer to pointers.

-

If you want the bytes of each string sequentially, you will have to loop through them and copy them into a buffer.

From

cstring

to

string

-

string(cs)-

Action : Alias.

-

-

strings.clone_from_cstring(cs)-

Action : Copy.

-

From

cstring

to

rune

-

.

From

cstring

to

[]rune

-

.

From

cstring

to

byte

-

.

From

cstring

to

[]byte

-

.

From

cstring

to

[^]byte

-

transmute([^]byte)cs-

Action : Alias.

-

From

[]byte

to

string

-

string(bs)-

Unless it's a slice literal

-

Action : Alias.

-

-

transmute(string)bs-

Action : Alias.

-

From

[]byte

to

cstring

-

.

From

[]byte

to

rune

-

.

From

[]byte

to

[]rune

-

.

From

[]byte

to

[^]byte

-

raw_data(bs)

From

byte

to

string

last_character_as_byte := my_str[len(my_str) - 1]

string([]byte{ last_character_as_byte })

From

byte

to

cstring

-

.

From

byte

to

rune

-

.

From

rune

to

string

-

With a

strings.Builder:-

strings.write_rune

-

bytes, length := utf8.encode_rune(r)

string(bytes[:length])

-

utf8.encode_rune+ slice using theintreturned, to perform astring()cast. -

No allocation is needed.

From

rune

to

[]byte

-

utf8.encode_rune-

Takes a

runeand gives you a[4]u8, intwhich you can slice and string cast.

-

From

[]rune

to

string

-

-

"C Byte Slice".

-

Action : Copy.

-

From

[^]byte

+ length to

string

-

strings.string_from_ptr(ptr, length)-

Action : Alias.

-

From

[^]byte

to

cstring

-

cstring(ptr)-

"C Byte Slice".

-

Action : Alias.

-

From

struct

to

[^]byte

-

cast([^]u8)&my_struct

From

struct

to

[]byte

-

(cast([^]u8)&my_struct)[:size_of(my_struct)] -

mem.ptr_to_bytes(ptr, len)-

Creates a byte slice pointing to

lenobjects, starting from the address specified byptr. -

It just does

transmute([]byte)Raw_Slice{ptr, len*size_of(T)}internally.

-

type / typeid / size_of

Type

-

-

Strange.

-

-

Get the type of a variable :

typeid_of(type_of(parse)) -

Places using

exprortype:-

base:builtintype_of :: proc(x: expr) -> type --- -

base:intrinsics:soa_struct :: proc($N: int, $T: typeid) -> type/#soa[N]T type_base_type :: proc($T: typeid) -> type --- type_core_type :: proc($T: typeid) -> type --- type_elem_type :: proc($T: typeid) -> type --- type_integer_to_unsigned :: proc($T: typeid) -> type where type_is_integer(T), !type_is_unsigned(T) --- type_integer_to_signed :: proc($T: typeid) -> type where type_is_integer(T), type_is_unsigned(T) ---

-

typeid

-

typeid. -

typeid_of($T: typeid) -> typeid.-

Strange.

-

-

Example :

-

Caio:

-

Why isn't this allowed?

id: typeid = f32 data: int = 2 log.debugf("thing: %v", cast(id)data) -

I'm trying to understand a bit more about typeid.

-

I've seen it being used as a compile time known constant in generic procedures,

$T: typeid, and in this case it can be used for casting? How does this work?

-

-

GingerBill:

-

Because

castis a compile time operation. -

What you are doing requires an run time operation which is very difficult to do.

-

-

Barinzaya:

-

A proc argument like

$T: typeidis parapoly , which means it's basically a generic/template argument. -

The compiler will generate a separate variation of the proc for every unique group of parapoly arguments it's called with.

-

Naturally, that means that the argument must be known at compile-time, so it can't be a variable.

-

-

Caio:

-

hmmm ok. So, a brief of what I was thinking of doing: I'm trying to store some data in a struct in its generic form, and then use some other data to cast it back to the original data. A

anystores exactly what I need: arawptrand a type, but I got confused about thetypeid. Is there a way to accomplish this operation?

-

-

Barinzaya:

-

You basically have to just type switch on the

anyand handle the cases that you care about, e.g. howfmthandles arguments: https://github.com/odin-lang/Odin/blob/38faec757d4e4648a86fb17a1fda0e2399a3ea19/core/fmt/fmt.odin#L3168.

base_arg := arg // is an any. base_arg.id = runtime.typeid_base(base_arg.id) // probably to avoid derivative types `my_int :: int`, something like that. switch a in base_arg { case bool: fmt_bool(fi, a, verb) case b8: fmt_bool(fi, bool(a), verb) case b16: fmt_bool(fi, bool(a), verb) case b32: fmt_bool(fi, bool(a), verb) case b64: fmt_bool(fi, bool(a), verb) case any: fmt_arg(fi, a, verb) case rune: fmt_rune(fi, a, verb) // etc }-

A

unionis usually better unless you really need to handle anything.anyis a pointer that doesn't behave like a pointer and is easy to misuse; aunionactually contains its value. Cases needing true generic handling are rare, usually for arbitrary (de)serialization and printing.

-

-

Jesse:

-

anyshould be avoided until all other alternatives have been explored. -

It is almost never the case that you really don't know what set of types some data could be.

-

-

size_of

-

Why do I get a different value for

size_of, betweenbar1andbar2?Vertex :: struct { pos: [2]f32, color: [3]f32, } foo :: proc(array: []$MEMBER) { // passing a `[]Vertex` as a parameter fmt.println(size_of(MEMBER)) // prints 20 bar1(MEMBER) bar2(MEMBER) } bar1 :: proc(member: typeid) { fmt.println(size_of(member)) // prints 8 } bar2 :: proc($member: typeid) { fmt.println(size_of(member)) // prints 20 }-

bar1is thetypeidofVertex, notVertex, so it's getting the size of atypeid. -

typeidis the type of types. It's a hash of the type's canonical name. At compile time the compiler knows what the underlying type is, so it'll use the type itself rather thantypeid. At runtime it can't know, so it'll be atypeid. -

Compile-time

typeids are effectively types (which is why you can do stuff likeproc ($T: typeid) -> T), whereas run-timetypeids are indeed just an ID (u64-sized).

-

any

-

any. -

Raw_Any. -

It is functionally equivalent to

struct {data: rawptr, id: typeid}with extra semantics on how assignment and type assertion works. -

The

anyvalue is only valid as long as the underlying data is still valid. Passing a literal to ananywill allocate the literal in the current stack frame.

Comparison

any

vs

union

-

anyis a topologically-dual to aunionin terms of its usage.-

Both support assignments of differing types (

anybeing open to any type,unionbeing closed to a specific set of types). -

Both support type assertions (

x.(T)). -

Both support

switch in.

-

-

The main internal difference is how the memory is stored.

-

A

anybeing open is a pointer+typeid, aunionis a blob+tag. -

A

uniondoes not need to store atypeidbecause it is a closed ABI-consistent set of variant types.

-

Structure

Raw_Any :: struct {

data: rawptr, // pointer to the data

id: typeid, // type of the data

}

@(require_results)

any_data :: #force_inline proc(v: any) -> (data: rawptr, id: typeid) {

return v.data, v.id

}

Storing data

-

It always stores a pointer to the data.

-

anyonly works by having a pointer to something. This something can be stored in the heap or on the stack. -

If the data is already stored somewhere the operation is more direct, otherwise a temp variable is created on the stack and a pointer to this temp variable is used instead.

-

The only way to make

anyhold a value that outlasts the stack, the value needs to be stored in the heap. This is needed as ananyonly stores a pointer to something; this indirection makes things a quite more annoying.

Loose examples

-

The value is already stored :

x: int = 123

a: any = x

// equivalent to

a: any = { data = &x, id = typeid_of(type_of(x)) }

x: ^int = new(123)

a: any = x

// equivalent to

a: any = { data = &x, id = typeid_of(type_of(x)) }

-

The value is not yet stored :

a: any = 123

// equivalent to

_tmp: int = 123 // variable created on the stack

a: any = { data = &_tmp, id = typeid_of(type_of(_tmp)) }

x: int = 123

a: any = &x

// equivalent to

_tmp: ^int = &x // variable created on the stack

a: any = { data = &_tmp, id = typeid_of(type_of(_tmp)) }

Storing a pointer to something on the stack

-

It's possible to get a pointer to the value (the value is stored):

-

Assigning implicitly:

-

x: int = 123; a: any = x-

xis a value on the stack. -

astoresa.data = &x, which is a pointer to the value on the stack .

-

-

x: ^int = &i; a: any = x-

iis a value on the stack. -

xstores a pointer to something on the stack. -

astoresa.data = &x, which is a pointer to something on the stack , to a pointer to something on the stack.

-

-

x := make([]int, 3); a: any = x-

xis a array slice on the stack, that stores a pointer to something on the heap. -

astoresa.data = &x, which is a pointer to the array slice on the stack , which then points to the heap. -

This is a really weird one, but

xis indeed on the stack, as mentioned by 'Barinzaya' and 'rats'.

-

-

x: ^int = new_clone(123); a: any = x-

xis a pointer to the heap. -

astoresa.data = &x, which is a pointer on the stack , to a pointer on the heap.

-

-

-

Assigning explicitly (storing directly into the

.datafield):-

x: ^int = &i; a: any = { data = x, id = typeid_of(int) }-

iis a value on the stack. -

xstores a pointer to something on the stack. -

astores a pointer to something on the stack . -

Note how an indirection is removed, when comparing to

x: ^int = &i; a: any = x.

-

-

-

-

It's not possible to get a pointer to the value (the value is not stored):

-

Assigning implicitly:

-

awill always storea.data = &_tmp, where_tmpis on the stack; therefore, it always stores a pointer to the stack , due to the indirection of&_tmp. -

a: any = 123-

123is a literal, not yet stored. -

_tmp: int = 123. -

astoresa.data = &_tmp, which is a pointer to something on the stack .

-

-

x: int = 123; a: any = &x-

&xis a pointer tox; the value is stored, but the pointer is not yet stored. -

_tmp: ^int = &x. -

astoresa.data = &_tmp, which is a pointer to something on the stack , to a pointer to something on the stack.

-

-

a: any = new_clone(123)-

new_clone(123)is a pointer to123on the heap; the value is stored on the heap, but the pointer is not yet stored. -

_tmp: ^int = new_clone(123). -

astoresa.data = &_tmp, which is a pointer to something on the stack , to a pointer to something on the heap.

-

-

-

Assigning explicitly (storing directly into the

.datafield):-

a: any = { data = &i, id = typeid_of(int) }-

Is the same case as

x: ^int = &i; a: any = { data = x, id = typeid_of(int) }, but removing the need forx.

-

-

-

Storing a pointer to something on the heap

-

It's possible to get a pointer to the value (the value is stored):

-

Assigning implicitly:

-

x := make([]int, 3); a: any = x[2]-

xis a array slice on the stack, that stores a pointer to something on the heap. -

astoresa.data = &x[2], which is a pointer to something on the heap . -

Even though

xis on the stack,x[i]is a value on the heap, so&x[i]is a pointer on the heap.

-

-

-

Assigning explicitly (storing directly into the

.datafield):-

x: ^int = new_clone(123, context.temp_allocator); a: any = { data = x, id = typeid_of(int) }-

xstores a pointer to something on the heap. -

astores a pointer to something on the heap.-

This is not the same as doing:

x: ^int = new_clone(123) a: any = x-

astores a pointer toxon the stack, which stores a pointer to something on the heap.

-

-

-

Note how

idneeds to beint, whilex: ^int. -

When unwrapping the data, we'll get an

int, not the original^int. -

The original

^intcan actually be retrieved by doing(cast(^int)a.data), instead of(cast(^int)a.data)^; this has to be done manually.-

The second option is done automatically by

a.(int). -

Doing something like

a.(^int)in this case will just cause a failure, as(cast(^^int)a.data)^is not valid; the data is not^^int, but^int.

-

-

If the original

^intis not retrieved, then the pointer is lost and the memory cannot be freed; to avoid this, this technique should use of arena allocators, such ascontext.temp_allocator. -

(2025-11-08)

-

I tested this and it worked correctly:

batch := new_clone(Batch(T){ index = i32(i), offset = i32(offset), data = data[offset:min(offset + max_batch_size, len(data))], }, context.temp_allocator) args[0] = { data = batch, id = typeid_of(Batch(T)) } -

-

-

-

-

It's not possible to get a pointer to the value (the value is not stored):

-

Assigning implicitly:-

This makes a

_tmpbe created, which will always be on the stack, so this is not possible if you want to store a pointer to something on the heap.

-

-

Assigning explicitly (storing directly into the

.datafield):-

a: any = { data = new_clone(123, context.temp_allocator), id = typeid_of(int) }-

Same case as

x: ^int = new_clone(123, context.temp_allocator); a: any = { data = x, id = typeid_of(int) }, but removing the need forx.

-

-

-

About array/slices with

any

-

Barinzaya:

-

A slice is a pointer and length, in

x := make([]int)xwould still be on the stack.

-

-

Rats:

-

Variables are always on the stack.

-

You can't have a "heap allocated variable", but you can have a variable holding a pointer into the heap.

-

-

Barinzaya:

-

That's what

xis. The actual data in the slice is behind the pointer, and can be anywhere (heap, stack, mapped file, static data, etc.) -

A slice is ultimately just a kind of pointer, it just points to an array of a variable number of things rather than just one thing

-

-

Caio:

-

is it possible to do something like

x := make([]int); a: any = x.data, so thea.data = &x.data, which then is a pointer to the heap?

-

-

Barinzaya:

-

Kind of, but you wouldn't be able to keep the length

-

That's basically what

a: any = x[0]would do -- it would store a pointer to the first element in the backing data. But it loses the length. -

If you knew the length, you could "rebuild" the slice, but

anywon't really help with that.

-

-

Caio:

-

so then, there's no way for me to store a whole array inside a

any?

-

-

Barinzaya:

-

You'd have to allocate the slice itself too

x_data := make([]int, 4) x := new_clone(x_data) a: any = x^-

But that means you need to handle

deleteing/freeing both levels of indirection. If you're getting to that point, maybe it's time to reconsider why you need that.

-

Getting the underlying value

-

(cast(^T)a.data)^is the same asa.(T). -

Barinzaya:

-

Also asserting the

id, but otherwise yes, they are the same.

-

-

Not possible:

-

(cast(^(a.id))a.data)^ -

or

-

a.(a.id) -

As the

.idid runtime known, not comp-time known.

-

Using

.()

My_Struct :: struct{

x: int,

y: intrinsics.Atomic_Memory_Order,

}

main :: proc() {

{

a: int = 123

b: any = a

c := b.(int)

fmt.printfln("a: %v, b: %v, c: %v", a, b, c)

}

{

a: [4]bool

b: any = a

c := b.([4]bool)

fmt.printfln("a: %v, b: %v, c: %v", a, b, c)

}

{

a := make([dynamic]My_Struct, context.temp_allocator)

append(&a, My_Struct{}, My_Struct{ 2, .Relaxed })

b: any = a

c := b.([dynamic]My_Struct)

fmt.printfln("a: %v, b: %v, c: %v", a, b, c)

}

{

a := make([dynamic]My_Struct, context.temp_allocator)

append(&a, My_Struct{}, My_Struct{ 2, .Relaxed })

b: any = a[:]

c := b.([]My_Struct)

fmt.printfln("a: %v, b: %v, c: %v", a, b, c)

}

}

-

a,bandchere are always printed the same, whilechas the type ofa.

Using

switch v in a {}

-

ais theanyvariable. -

vis the unwrapped value.

a: any = 123

switch v in a {

case int:

fmt.printfln("Is int. Value: %v", v)

// prints "Is int. Value: 123"

case []byte:

}

Using the

reflect

procedures

-

They do the same operation as shown, but fancier.

-

as_bool. -

as_bytes.@(require_results) as_bytes :: proc(v: any) -> []byte { if v != nil { sz := size_of_typeid(v.id) return ([^]byte)(v.data)[:sz] } return nil } -

as_f64. -

as_i64. -

as_u64. -

as_int. -

as_uint. -

-

Attempts to convert an

anyto arawptr. -

This only works for

^T,[^]T,cstring,cstring16based types.

// Various considerations first. result = (^rawptr)(any_value.data)^ -

-

-

Returns the equivalent of doing

raw_data(v)wherevis a non-any value

// Various considerations first. result = any_value.data -

Etc

Is

-

is_nil.-

Returns true if the

anyvalue is eithernilor the data stored at the address is all zeroed

-

Etc

-

deref.-

Dereferences

anyif it represents a pointer-based value (^T -> T)

-

-

-

Returns the name of enum field if a valid name using reflection, otherwise returns

"", false

-

-

equal.-

Checks to see if two

anyvalues are semantically equivalent

-

-

-

Returns the underlying variant value of a union. Panics if a union was not passed.

-

-

-

UNSAFE: Returns the underlying tag value of a union. Panics if a union was not passed.

-

-

index.-

Gets the value by an index, if the type is indexable. Returns

nilif not possible

-

Examples

-

See the example below about

typeids.

Primitive Types

bool

-

bool .

-

Has a size of 1

byte(b8).

bool

-

Other bools:

b8 b16 b32 b64-

"The only world where you would use one of these other bools is if you are making a binding for another language that has different sized bool types."

-

boolis equivalent tob8.

-

nil

-

Types that support

nil:-

rawptr -

any -

cstring -

typeid -

enum -

bit_set -

Slices

-

procvalues -

Pointers

-

#soaPointers -

Multi-Pointers

-

Dynamic Arrays

-

map -

unionwithout the#no_nildirective -

#soaslices -

#soadynamic arrays

-

rawptr

-

rawptr .

-

All pointers can implicitly convert to

rawptr.

integer

-

“natural” register size.

-

Is guaranteed to be greater than or equal to the size of a pointer.

-

When you need an integer value, you should default to using

intunless you have a specific reason to use a sized or unsigned integer type

int uint -

-

Specific sizes:

i8 i16 i32 i64 i128 u8 u16 u32 u64 u128 -

Pointer size:

uintptr -

Endian-specific integers:

// little endian i16le i32le i64le i128le u16le u32le u64le u128le // big endian i16be i32be i64be i128be u16be u32be u64be u128be

float

-

No need to use

fin front of the float.

f16 f32 f64

-

Endian-specific floating point numbers:

// little endian f16le f32le f64le // big endian f16be f32be f64be

rune

-

Signed 32-bit integer.

-

Represents a Unicode code point.

-

Is a distinct type from

i32.

rune

Math Types

Matrix

-

Matrix .

Creation

m: matrix[2, 3]f32

m = matrix[2, 3]f32{

1, 9, -13,

20, 5, -6,

}

Layout

Clarification

-

Rows and Columns begin at 0.

-

"column 1" means the 2nd column.

-

Same as an array.

Representation

[x, y]

-

The representation

m[x, y]is always the same regardless of the layout (column-major vs row-major).

// row 1, column 2

elem := m[1, 2]

Representation

[x]

-

Will return an array of the values in that column/row, whichever is major .

-

For column-major (default):

// column 1

elem := m[1]

-

For row-major (with

#row_major):

// row 1

elem := m[1]

Representation

[x][y]

-

m[x][y]is justm[x]and then indexing theyth value in the array. If the layout ofm[x]changes, so does this; in other words, this representation is affected by the layout. -

For column-major (default):

// column 1, row 2

elem := m[1][2]

-

For row-major (with

#row_major):

// row 1, column 2

elem := m[1][2]

Operations

-

matrix4_perspective-

Clip Space Z Range:

-

[-1 to +1], just like OpenGL.

-

-

Clip Space Y:

-

Y Up, just like OpenGL (Vulkan is Y Down).

-

-

Handedness:

-

If

flip_z_axisistrue:-

Right-handed coordinate system (camera forward is -Z).

-

-

If

flip_z_axisisfalse:-

Left-handed coordinate system (camera forward is +Z).

``

-

-

-

Quaternion

type

-

-

Is the set of all complex numbers with

f16/f32/f64real and imaginary (i,j, &k) parts.

-

quaternion64 quaternion128 quaternion256

-

-

fN->quaternion4N(e.g.f32->quaternion128) -

complex2N->quaternion4N(e.g.complex64->quaternion128)

-

Interpretation

-

"It's a bit odd that the value is an operation. It's just a very mathematical approach to it. It's basically an extension of how complex numbers are written mathematically, e.g.,

1 + 2i". -

"It's more just syntax sugar for setting its fields, I think".

rot: quaternion128 = quaternion(x=0, y=0, z=0, w=1) // arguments must be named, to avoid ambiguity

rot: quaternion128 = 1 + 0i + 0j + 0k // this is valid.

-

rot: quaternion128 = 1, same as1 + 0i + 0j + 0k.-

This is the identity quaternion.

-

-

rot: quaternion128 = 0, same as0 + 0i + 0j + 0k.

Procedures

-

Quaternion from X :

-

-

(real, imag, jmag, kmag: Float) -> (Quaternion_Type)

-

-

-

(f: f32) -> (quaternion128)

-

-

-

(m: matrix[3, 3]f32) -> (quaternion128)

-

-

-

(m: matrix[4, 4]f32) -> (quaternion128)

-

-

-

quaternion_from_matrix.... -

quaternion_from_scalar....

-

-

-

Quaternion from angle :

-

-

(angle_radians: f32, axis: [3]f32) -> (quaternion128)

-

-

Using

quaternion_angle_axis, specifying the axis automatically:-

quaternion_from_euler_angle_x.-

(angle: f32) -> (quaternion128)

-

-

quaternion_from_euler_angle_y.-

(angle: f32) -> (quaternion128)

-

-

quaternion_from_euler_angle_z.-

(angle: f32) -> (quaternion128)

-

-

-

Using

quaternion_from_euler_angle_x/y/z, specifying the operation order:-

quaternion_from_euler_angles.-

(t1, t2, t3: f32, order: Euler_Angle_Order) -> (quaternion128)

-

-

-

quaternion_from_pitch_yaw_roll.-

(pitch, yaw, roll: f32) -> (quaternion128) -

Interestingly, does not use any of the above procedures.

-

.

.

-

-

-

Quaternion from vectors3 :

-

quaternion_from_forward_and_up.-

(forward, up: [3]f32) -> (quaternion128)

-

-

-

(eye, centre: [3]f32, up: [3]f32) -> (quaternion128)

-

-

quaternion_between_two_vector3.-

(from, to: [3]f32) -> (quaternion128)

-

-

-

Quaternion to quaternion

-

-

(q: quaternion128, v: [3]f32) -> ([3]f32)

-

-

-

(a, b: quaternion128, t: f32) -> (quaternion128)

-

-

-

(x, y: quaternion128, t: f32) -> (quaternion128)

-

-

-

(q1, q2, s1, s2: quaternion128, h: f32) -> (quaternion128)

-

-

-

(quaternion128) -> (quaternion128)

-

-

-

(quaternion128) -> (quaternion128)

-

-

-

X from quaternion :

-

real. -

imag. -

jmag. -

kmag. -

conj. -

-

(q: quaternion128) -> (f32)

-

-

-

(q: quaternion128) -> (angle: f32, axis: [3]f32)

-

-

euler_angles_from_quaternion.-

(m: quaternion128, order: Euler_Angle_Order) -> (t1, t2, t3: f32)

-

-

-

(q: quaternion128) -> ([3]f32)

-

-

pitch_yaw_roll_from_quaternion.-

(q: quaternion128) -> (pitch, yaw, roll: f32)

-

-

-

(q: quaternion128) -> (f32)

-

-

-

(q: quaternion128) -> (f32)

-

-

-

(q: quaternion128) -> (f32)

-

-

Complex

type

-

complex .

complex32 complex64 complex128

Interpretation

-

"It's a bit odd that the value is an operation. It's just a very mathematical approach to it. It's basically how complex numbers are written mathematically, e.g.,

1 + 2i."

Procedures

Strings

-

Strings .

Types

-

string-

Used as default when doing type inference:

my_string := "hello". -

Stores the pointer to the data and the length of the string.

-

-

cstring-

"A little longer, with a 0 at the end".

-

Is used to interface with foreign libraries written in/for C that use zero-terminated strings.

-

Syntax

"string"

'rune'

`multiline_string`

Manipulation

import "core:strings"

-

If there is allocation,

deleteis used. -

Compare :

value: int = strings.compare("hello", "hi") -

Contains :

flag: bool = strings.contains("hello", "hi") // "hi" is in "hello" -

Concatenate :

my_string, err := strings.concatenate({"hello", "hi"}) defer delete(my_string) -

Upper :

my_string := strings.to_upper("hello") defer delete(my_string) -

Lower :

my_string := strings.to_lower("hello") defer delete(my_string) -

Cut :

-

"substring", "make the string smaller".

my_string, err := strings.cut("hello", 3, 5) // (string, first_idx, last_idx) defer delete(my_string) -

Slicing

-