Memory

Virtual Memory

-

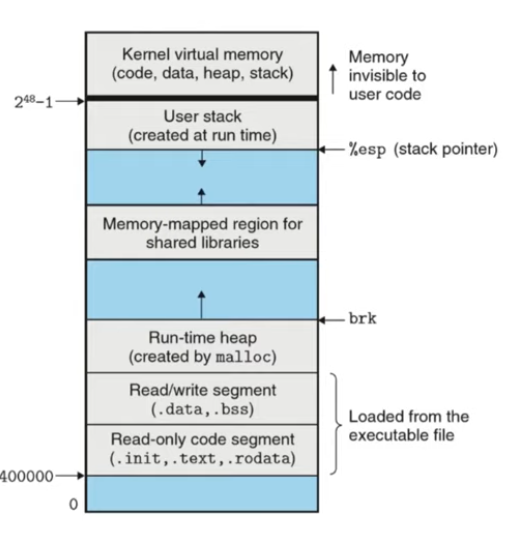

Modern operating systems virtualize memory on a per-process basis. This means that the addresses used within your program/process are specific to that program/process only.

-

Memory is no longer this dualistic model of the stack and the heap but rather a monistic model where everything is virtual memory.

-

Some of that virtual address space is reserved for procedure stack frames, some of it is reserved for things required by the operating system, and the rest we can use for whatever we want.

-

Memory is virtually-mapped and linear, and you can split that linear memory space into sections.

-

"A process view of memory".

-

Virtual memory is "merely" the way the OS exposes memory to user-space applications. It is not how most allocators work.

-

For the most part, one can simplify the concept of virtual memory down to "I ask the OS for a block of memory that is a number of pages in size", where a "page" is defined by the OS. Modern systems often have it as 4096 bytes. You'll say you want 8 pages, and the OS gives you a pointer to the first byte in a

8*4096byte block to use. You can also do things like set whether each page is readable, writable, executable, etc. -

And, as you alluded to initially, each page can be resident or not. So to say, actually backed by physical memory, or only theoretically set up for access however you've not touched it yet.

-

My current understanding:

-

(2025-11-14)

-

when calling

new()ormake()with the default heap allocator (context.allocator), Odin internally callsmalloc/calloc(at least on Unix) which internally callsmmapto reserve a chunk of virtual memory (4MiB (is it maybe 4KB?) in x86_64), which is only physically allocated when touching the memory on read/write (in Odin I assume this is done immediately as for ZII). Anew(int)is allocated inside a free slot list inside a run inside the chunk; apparently something like 16B for anint(this sounds weird to me as it can lead to 8B of waste in a 64bit system). -

For heap-allocated arenas in Odin, it seems like you need to create a buffer using a heap allocator before you can use the arena, which was confusing to me at first, but it makes sense now. I just see them now as a "managed slice of bytes in memory" inside the allocated region from the heap allocator.

-

-

.

.

-

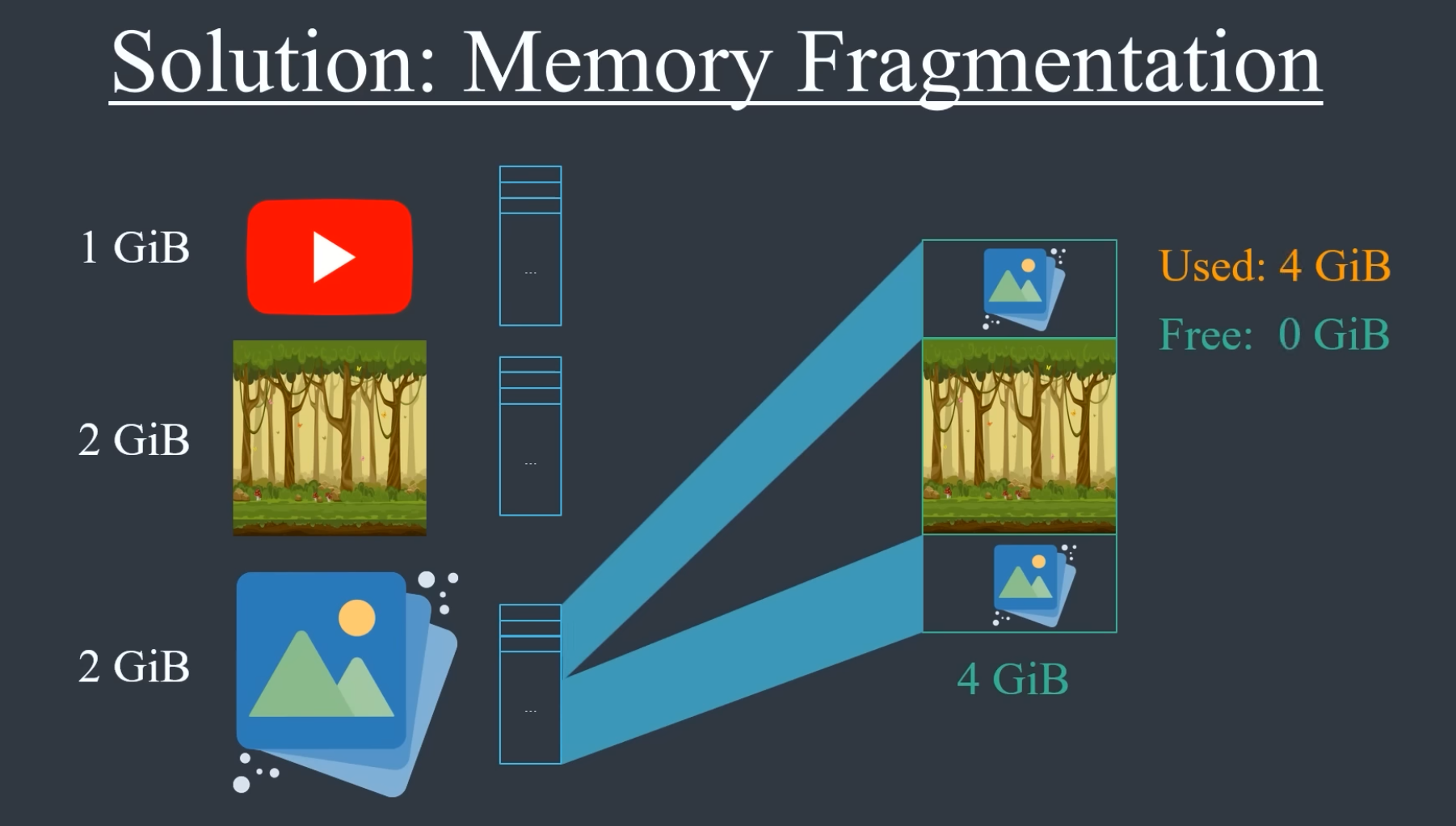

The program still assumes the memory is continuous.

-

.

.

-

-

The whole video is really cool.

-

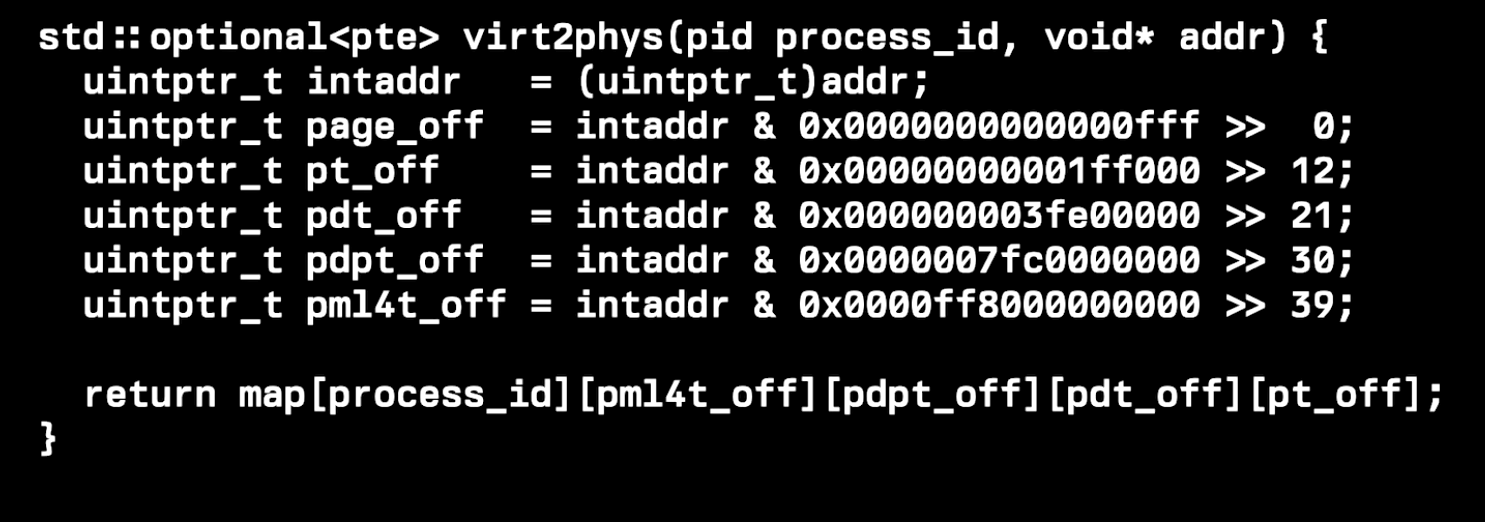

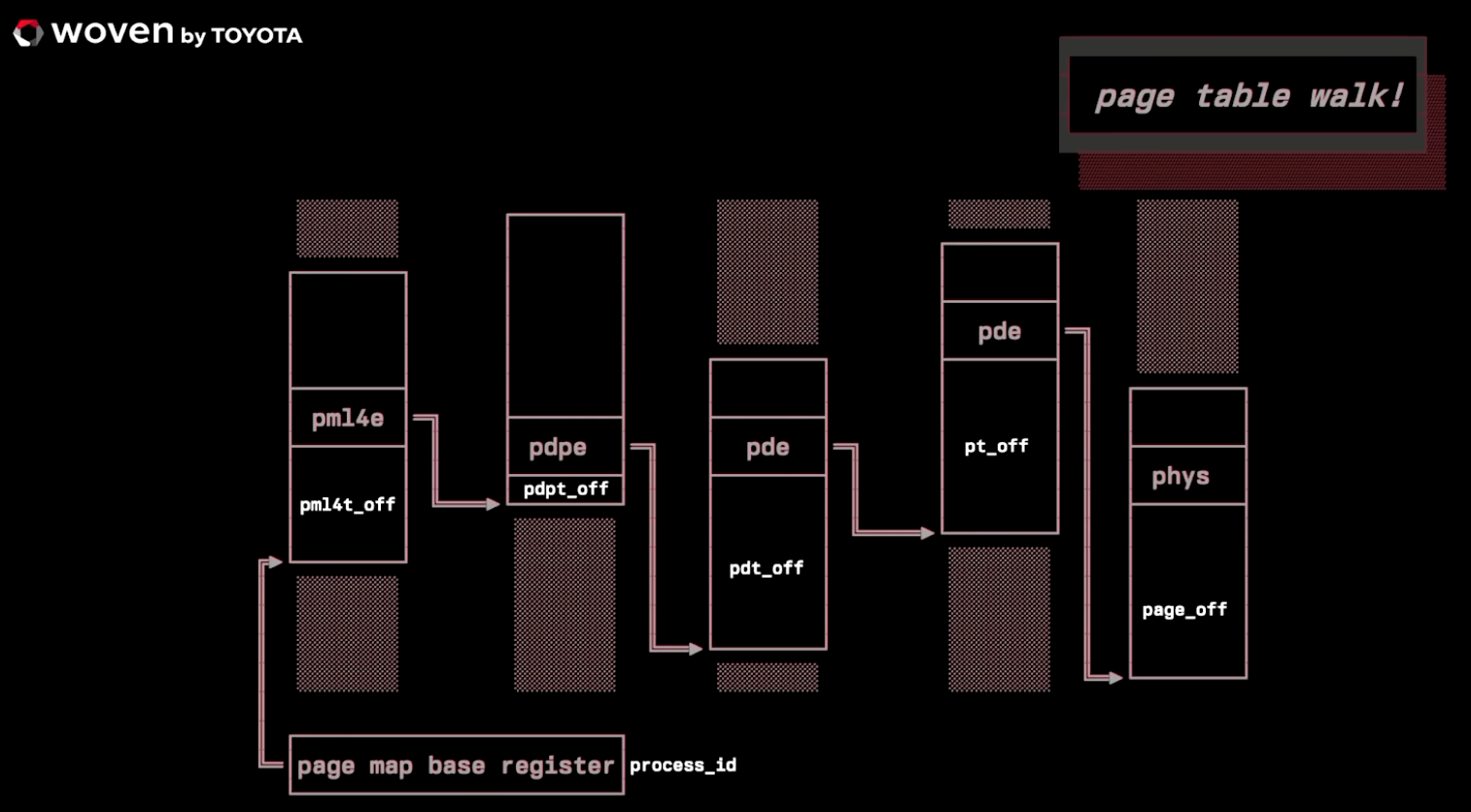

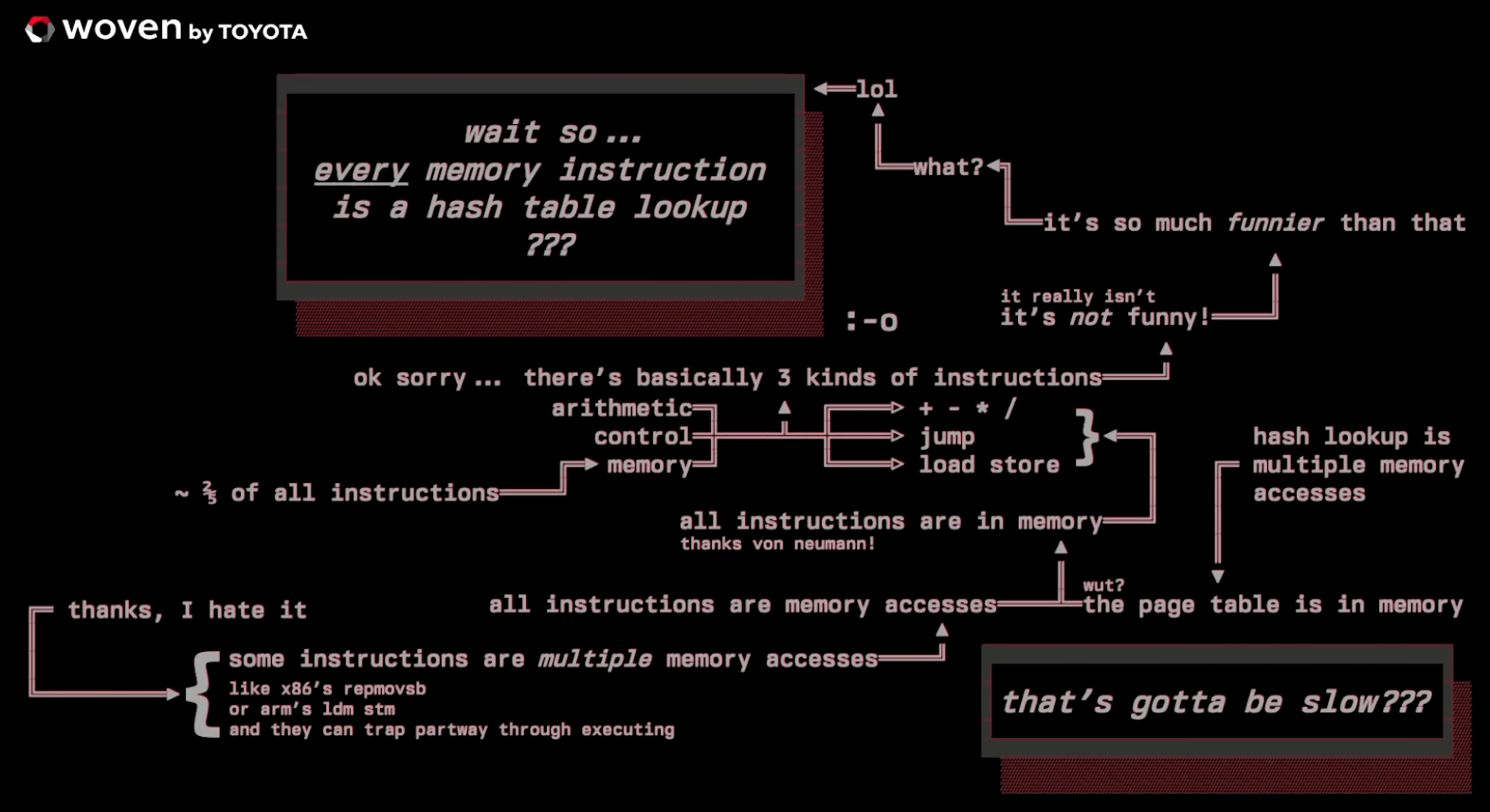

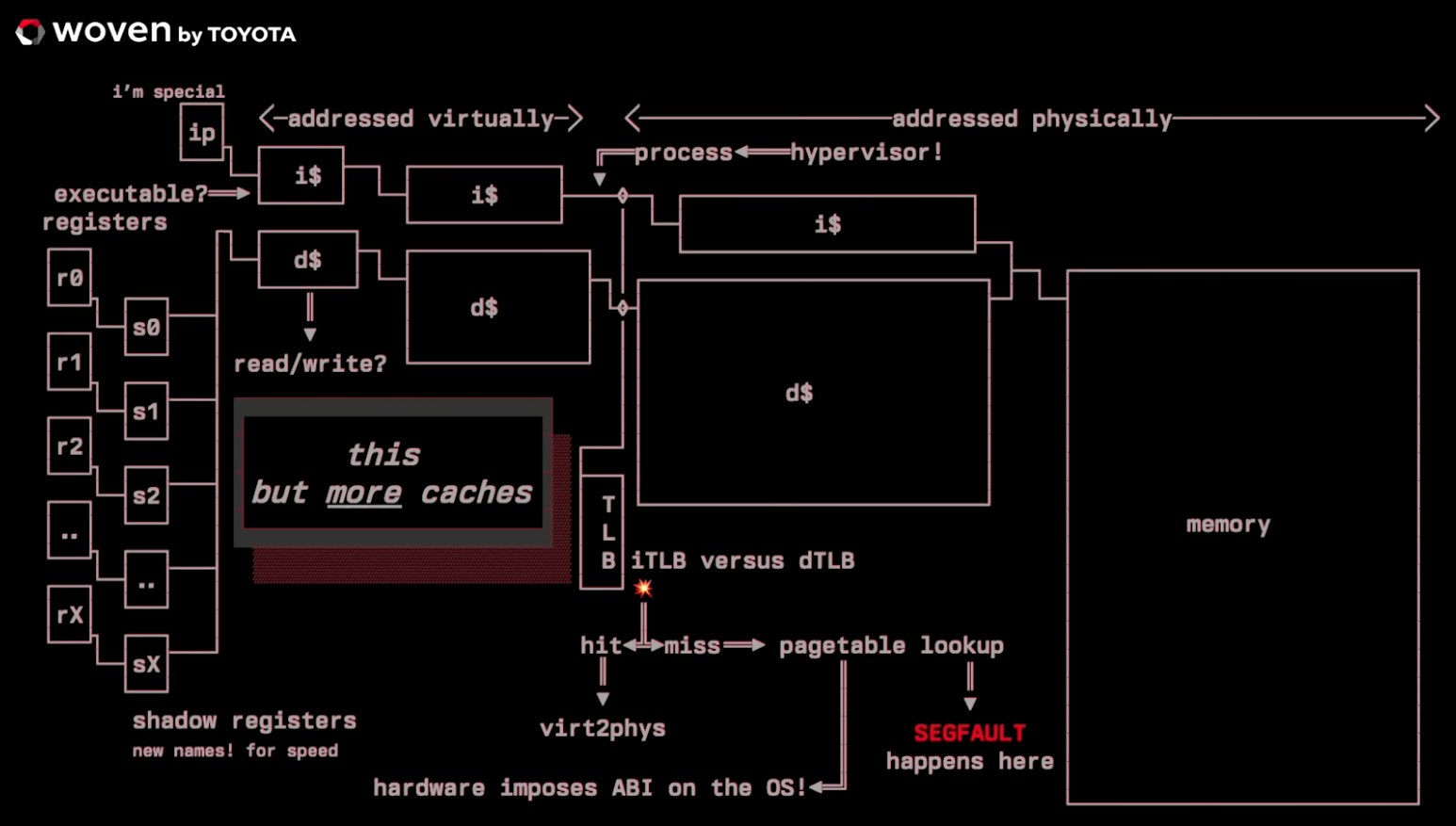

{28:30} He starts talking about Virtual Memory.

-

.

.

-

.

.

-

..

..

-

.

.

-

.

.

-

Caches make all this thing described work.

-

.

.

-

-

The magic of the page fault: understanding demand paging of virtual memory in linux .

-

Page tables for your page tables: understanding how multi level page tables work .

-

-

I haven't see the whole video. The content seemed distant to what I need right now.

-

Initial content

-

Caio:

-

"Even when allocator gets a mapped virtual range from the kernel, actual physical pages are usually allocated only when you touch them (page fault on first write/read). So

mmap/sbrkcreates virtual address space; the kernel populates physical pages on demand. Physical memory for those pages is usually committed lazily; when the process first touches a page, the kernel allocates a physical frame and updates the page tables." Or from the spec ofmalloc: Allocatessizebytes and returns a pointer to the allocated memory. The memory is not initialized . Ifsizeis 0, thenmalloc()returns a unique pointer value that can later be successfully passed tofree(). So what I got from both is that a page just has garbage at first, and doesn't actually have anything physical to it, just a virtual reservation of memory, but when writing to memory the OS would actually physically allocate that memory. So when I said "the act of Odin zeroing the memory would interact with the OS" I was referring to making the OS physically allocate the memory right away, not "lazily", if that makes sense.

-

-

"Not initialized" is like Odin's

---. It will be garbage. "Committing lazily" is about what I said before about being assigned to physical memory vs merely being set up for use. -

To be committed is to be resident is to be assigned to physical memory

-

but only use a few megs

-

why provide all of it

-

Some OSes (linux being a good example) allows overcommit

-

requesting memory from the OS is "the OS promises to give you the memory when you actually use it"

-

(nb: depends on the OS/configuration/etc)

-

Despite the fact that "being committed" means "assigned to physical memory", does that in fact mean that once you tell the OS to make some memory committed, that it will immediately appear in the task manager as taking up your RAM? You should create your own alloc and see what happens.

OS Pages

-

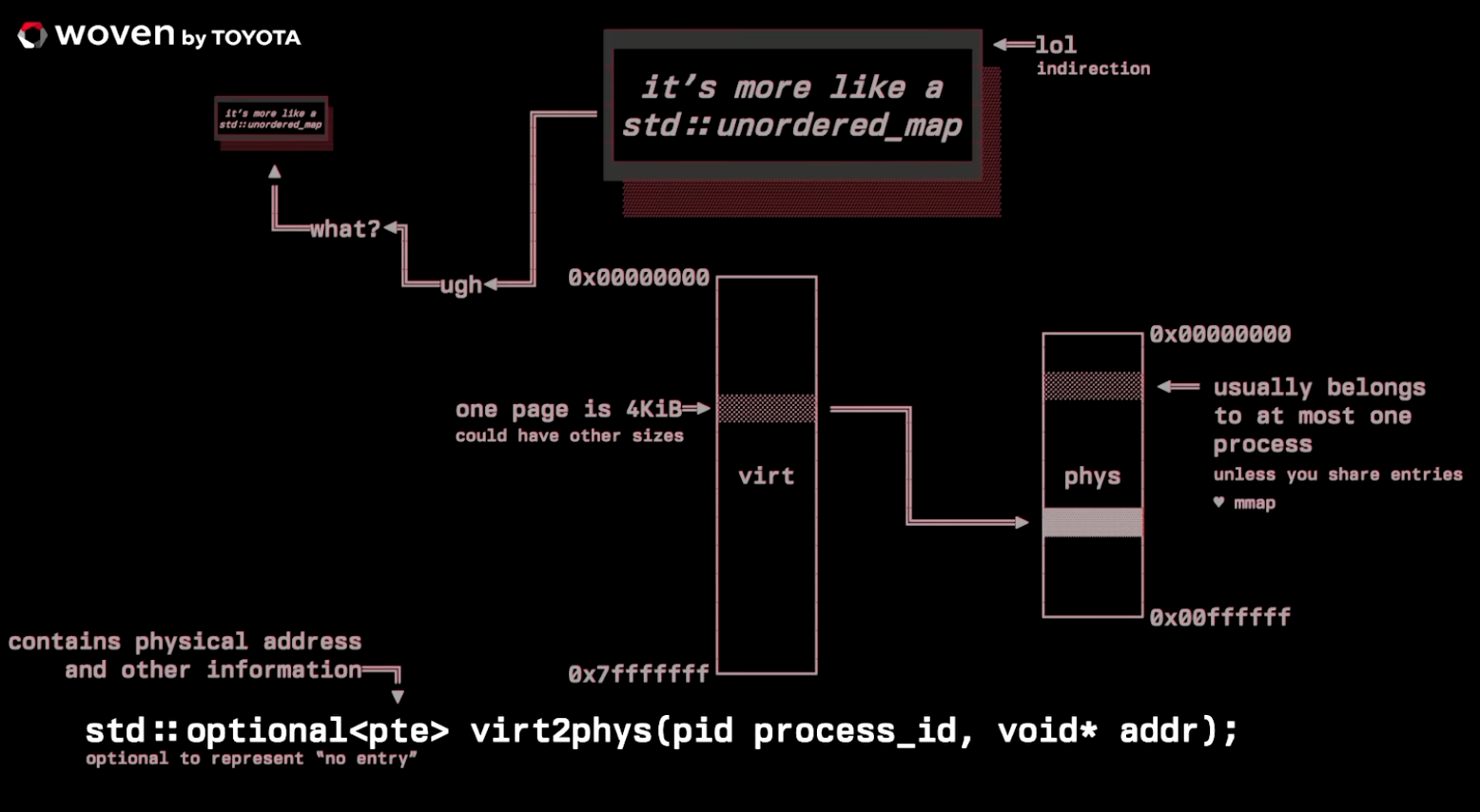

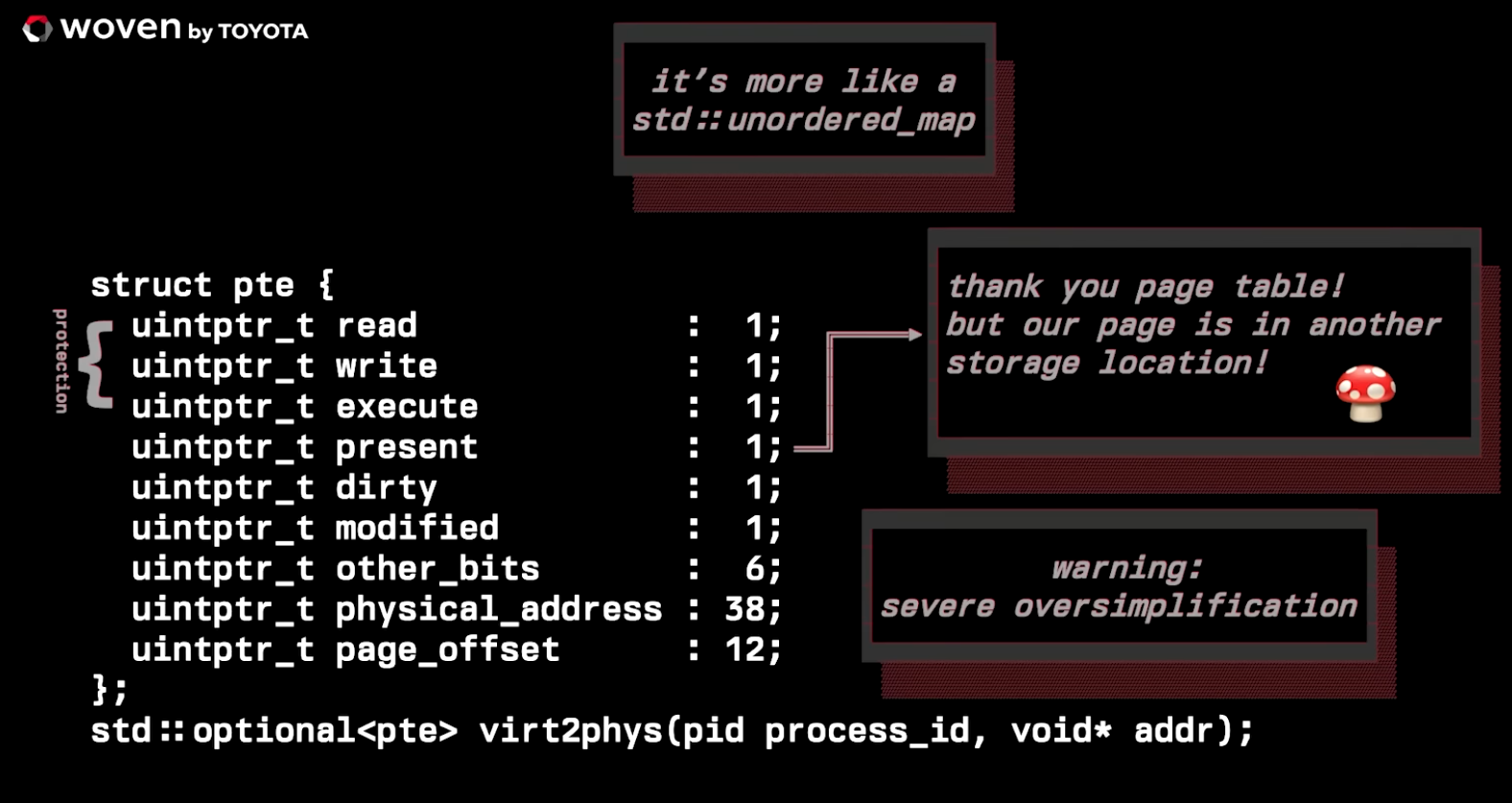

The page is the fundamental unit of virtual memory managed by the operating system and the CPU’s MMU (Memory Management Unit).

-

The kernel can only map, protect, or page-in/page-out whole pages. There’s no such thing as “half a page” to the MMU.

-

Pages are what the OS maps between virtual addresses (what your process sees) and physical memory (RAM).

-

When a process calls

mmap()orsbrk(), the OS reserves a region of virtual address space measured in pages. Physical memory for those pages is usually committed lazily — when the process first touches a page, the kernel allocates a physical frame and updates the page tables.

Typical size

-

CPU/kernel page size is usually 4 KiB on x86_64 — that’s the granularity the MMU uses.

Chunk

-

Pool of memory for suballocations.

-

A chunk is made up of many OS pages.

-

It's an allocator-internal bookkeeping unit — a larger contiguous region of virtual memory (often multiple pages) that the allocator manages.

-

It helps reduce syscall overhead. The allocator calls

mmap/sbrkonce to get a big chunk, then fulfills thousands of small allocations (1 B–1 KiB) from that memory by splitting it into bins or slabs. -

The allocator requests a contiguous virtual region (a chunk) and the OS provides that region in page-sized units.

-

The allocator only maps or expands its arena in chunk-sized (or threshold-driven) increments.

Typical size

-

glibc malloc:-

Variable, based on

brkormmapthresholds.

-

-

jemalloc:-

Often 4 MiB per chunk.

-

-

tcmalloc:-

Often 2 MiB per span.

-

-

Btw: 4 MiB chunk = 1024 OS pages.

Size class

-

Allocator rounds requested sizes up to a small set of sizes (e.g. 8, 16, 24, …, 1024, then larger classes).

-

Allocators round requested sizes up to a size class for alignment and bookkeeping simplicity.

-

Typical rules on 64-bit systems:

-

Minimum alignment/slot is often 8 or 16 bytes (16 is common on x86_64 for SIMD/alignment safety).

-

Sizes are rounded up into a small table of classes (e.g. 8,16,24,32,… or 16,32,48,64,… depending on allocator).

-

A run is created for a size class (e.g. 16 B slots); a page (4 KiB) then contains

4096 / 16 = 256slots.

-

-

Implication:

-

Each

intallocation carries internal fragmentation (unused bytes inside the slot). Anintis 4B, but uses a 16 B slot, that’s 12 B wasted per allocation (in-slot waste).

-

Run / span

-

A contiguous subrange of pages inside a chunk that the allocator uses for a particular size class.

-

One or more whole pages inside a chunk that the allocator dedicates to a single size class .

Bins / free lists

-

Per-size-class pools of free blocks ready to be returned for

mallocwithout splitting.

Slot / block / object

-

An individual allocation returned to the program (one slot inside a run).

-

They are the small pieces inside a run.

Illustration (ChatGPT)

-

Before any allocation:

Chunk (4 MiB) [ chunk header | page0 | page1 | page2 | ... | page1023 ] -

First allocation:

new int(4B → rounded to 16B)-

Allocator path:

-

Translate request size → size-class 16 B.

-

Look for an existing run for 16 B with free slots.

-

None yet in any chunk/arena, so allocator converts one page from the chunk into a run for the 16 B class. (This means the allocator marks page0 as a run and initializes its free-slot data: bitmap or free-list.)

-

Allocate the first slot (slot 0) from that run and return pointer

p = base_of_page0 + 0.

-

Chunk [ chunk header | page0: RUN(16B) [slot0=used, slot1..slot255=free] | page1 | ... ]-

Physical pages: if allocator zeroes the returned memory (language runtime

newsemantics), writing to the slot causes a page-fault and kernel provides a physical frame for page0. If allocator does not touch payload, that page may still be unbacked until first write.

-

-

Next few allocations: more small

new()calls:-

Each further

new(…)of size ≤16 B:-

Pop next free slot from page0’s free-list (slot1, slot2, ...).

-

No syscalls; purely allocator metadata ops (possibly lock-free if per-thread).

-

page0: RUN(16B) [slot0..slot9 = used, slot10..slot255 = free]-

Physical pages: once the program touches each used slot, page0's single physical frame services all those slots.

-

-

Run exhaustion: allocate the 257th small object

-

When page0’s 256 slots are all consumed:

-

Allocator sees the run is full.

-

It selects another free page inside the chunk (page1) and converts it into a new run for the 16 B size-class.

-

page1 gets initialized with its own free-list/bitmap; allocation returns page1 slot0.

-

[ chunk header | page0: RUN(16B) [all used] | page1: RUN(16B) [slot0=used, slot1..=free] | page2 ... ]-

Still no new

mmapsyscall — allocator used pages already reserved inside the chunk. If the chunk had no free pages left for runs, allocator wouldmmapa new chunk.

-

-

Mixed-size allocations appear later:

-

Suppose you then

malloc(1 KiB):-

Allocator maps that request to a larger size-class (say 1024 B).

-

It will allocate from a run/span dedicated to that class. If none exists:

-

It may grab one or more pages inside the same chunk and create a span for 1 KiB blocks. Example: one page can hold

4096 / 1024 = 4blocks.

-

-

If the large request exceeds the allocator’s “large” threshold it may instead call

mmapand give the caller an independent mapping (outside chunk).

-

[ chunk header | page0: RUN(16B) full | page1: RUN(16B) partly-used | page2: RUN(1KB) [blk0..blk3 some used] | page3: free page | ... ] -

-

Freeing behavior

-

Freeing a 16 B slot: allocator marks the slot free (pushes to free-list or clears bitmap). The page remains a run page. Usually the allocator does not

munmapa single partially-used page. -

When an entire run/span (one or more pages) becomes fully unused, allocator heuristics may decide to:

-

keep it for reuse (common), or

-

coalesce and

munmapthe pages to return virtual address space (or release them to a central pool). This is allocator-specific.

-

-

Virtual Memory Mapping

mmap

-

mmap(..) -

Tells the OS to allow read/write to a file/device as if it were in memory with byte 0 at a given address.

-

Even when allocator gets a mapped virtual range from the kernel, actual physical pages are usually allocated only when you touch them (page fault on first write/read). So

mmap/sbrkcreates virtual address space; the kernel populates physical pages on demand. -

It does not magically remember or manage allocator chunks — the allocator (e.g.

malloc, jemalloc, tcmalloc) is what tracks chunks and decides when to callmmapormunmap.mmapsimply asks the kernel to reserve/map a virtual-address region; the kernel records that region in its VM structures and returns the address. The allocator then sub-allocates from that region without further syscalls until it needs more space (or decides to return space).

brk

-

brk(..) -

shrink with

brkcan be used as "unmap".

sbrk

-

sbrk(..) -

Asks the OS to expand/contract the size of the valid memory.

-

"You get multiples of page size, one way or the other".

munmap

-

munmap -

Free pages, unmap.

Process

-

Your allocator (

malloc) decides it needs more virtual address space (its internal chunks/arenas are exhausted). -

The allocator issues a syscall (

mmapor sometimessbrk/brk) requesting a contiguous virtual region of some size (an allocator-chosen chunk, e.g. 4 MiB). -

The kernel creates a VMA (e.g.

vm_area_structon Linux) covering that range and returns the base address to the allocator. No physical pages are necessarily assigned yet — only virtual address space is reserved. -

The allocator records that new region in its own metadata (free lists, bitmaps, arena/chunk tables) and hands out pointers for subsequent

malloc/newrequests from that region — no furthermmapneeded while that region has free space. -

When the program first accesses pages inside the region the CPU triggers page faults and the kernel assigns physical frames (demand paging).

-

If the allocator later frees enough whole pages or decides it no longer needs the region, it may call

munmap(or shrink withbrk) to return the virtual range to the kernel.

OS: Memory on Windows

-

Demand-page memory management.

-

Process aren't "born" with everything it needs, it actually needs to ask the system for it.

-

The virtual memory is just a concept until the process touches the memory, demanding that the memory be backed with something physical.

-

There's almost no connection between virtual memory and physical memory; except by the bridge between the two (mapping).

-

There's no swap in Windows; it's a old technique for when a process goes idle, the OS would take it's memory and throw it out into the paging file.

-

A page is 4KB.

-

Page is defined by the hardware and the OS.

-

Allocations must align on 64KB boundaries.

-

Mysteries of Memory Management Revealed (Part 1/2) .

-

Virtual Memory.

-

-

Mysteries of Memory Management Revealed (Part 2/2) .

-

Physical Memory.

-

Talks about Working Set.

-

Process Address Space Management

-

How an operating system represents, backs, and shares ranges of a process’s virtual addresses.

-

The terminology used is Windows (Win32) specific.

-

Ex:

MEM_COMMIT,MEM_RESERVE,MEM_IMAGE,MEM_MAPPED,VirtualAlloc,VirtualQuery, Private Bytes, Working Set, Commit Charge,pagefile.

-

-

The concepts themselves are general OS virtual-memory concepts present on Linux, BSD, macOS, etc. Other OSes use different APIs and names but implement the same ideas.

-

Ex: reservation vs commit, file-backed vs anonymous, copy-on-write, resident set vs virtual size, sharable vs private.

-

-

A single memory region will have both a State and a Type .

Memory State (address-range lifecycle)

-

`MEM_COMMIT

-

Pages in that range have physical backing (pagefile and/or RAM) allocated (or will be charged to the process’ commit limit).

-

Represents memory that actually contains or will contain data.`

-

In Use.

-

Actually serves some purpose. It represents some data.

-

-

MEM_RESERVE(Windows) /mmap(..., PROT_NONE)(Linux)-

Address range is reserved in the virtual address space.

-

No physical backing (RAM/pagefile) is allocated yet.

-

Reservation prevents other allocations from taking those addresses.

-

Does not consume commit.

-

Can later be turned into committed pages.

-

Allocates an address range without faulting pages.

-

-

MEM_FREE-

Address range is unallocated and available for a new reservation/commit. Nothing mapped there.

-

Memory Type (what backs the pages)

-

MEM_IMAGE-

Executable images (EXE/DLL).

-

Mapped executable image (PE): your EXE and DLLs. File-backed by the image on disk (loaded by the loader).

-

Often reported as committed when pages are resident, but they are backed by the file on disk (not pagefile) unless they are written to and become private (COW).

-

Examples :

-

Executable + DLLs (Vulkan loader, driver DLLs, runtimes).

-

-

-

MEM_MAPPED-

File-mapped data (non-image).

-

A file mapping created with

CreateFileMapping/MapViewOfFile(non-image file). -

These are file-backed; they do not charge commit unless pages are privately modified (COW).

-

Examples :

-

mmapped asset packs, shader cache files, streamed textures, some driver mappings.

-

-

-

MEM_PRIVATE-

Private anonymous pages.

-

Anonymous/private memory (allocated with

VirtualAlloc(MEM_COMMIT)or via heap APIs). -

Pagefile-backed; increases commit charge and is counted as Private Bytes.

-

Examples:

-

Heaps, stacks, general

VirtualAllocprivate buffers (your allocators if they commit pages), CRT heaps, driver user-mode allocations that useVirtualAlloc(MEM_COMMIT)or heap APIs.

-

-

-

Working Set

-

The set of physical pages (RAM) currently resident for the process. Includes resident pages from image, mapped files and private committed pages.

-

It is a resident-RAM metric.

-

Can be smaller than commit.

-

-

Commit / Commit Charge (pagefile)

-

Amount of virtual memory that must be backed by the pagefile (or other backing store) across the system. Primarily driven by committed private pages. File-backed pages normally do not count against commit because they can be reloaded from the file on disk; they only count if they are made private (COW).

-

-

Virtual Size / Virtual Bytes

-

Amount of virtual address space reserved/used by the process (includes reserved ranges + committed ranges). Large reservations increase virtual size but do not increase commit.

-

Memory Property: Sharable

-

It is a property of some regions, not a type.

-

Shared pages :

-

A page is shared when:

-

It is backed by a file (image or file mapping).

-

It is identical across processes

-

Access permissions allow sharing (typically read-only or copy-on-write)

-

-

Shared pages do not count as private commit.

-

This corresponds to:

-

MEM_IMAGE -

MEM_MAPPED

-

-

Examples:

-

EXE/DLL code sections

-

Read-only memory-mapped assets

-

Read-only data from DLLs

-

Shader cache files mapped read-only

-

-

-

Private pages :

-

A page is private when:

-

It is backed by the

pagefile(anonymous memory). -

It cannot be shared with another process.

-

-

These pages contribute to Private Bytes and commit .

-

Corresponds to:

-

MEM_PRIVATE. -

COW versions of file-backed pages (after modification)

-

-

Examples:

-

Normal

VirtualAlloc(MEM_COMMIT)memory -

Heaps, stacks, arena allocators

-

Modified portions of an

mmappedfile or the image (COW)

-

-

-

MEM_IMAGE-

Always shareable until you write to a writable image section.

-

Backing is the image file on disk.

-

Multiple processes can map the same DLL and share the same physical pages.

-

The page stays shared if it comes from a DLL or EXE file with normal image layout.

-

-

MEM_MAPPED-

Always shareable until written.

-

By nature it is shareable, because it is file-backed.

-

Always sharable , but whether it is actually shared right now depends on whether another process maps the same file with compatible access.

-

It can change :

-

If you modify a

MEM_MAPPEDpage, it becomes private via COW. -

The original (on-disk) data remains shareable.

-

-

-

MEM_PRIVATE-

Backed by pagefile.

-

Not shareable between processes (unless you explicitly create shared memory using

CreateFileMapping(INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE, ...), but in that case Windows still reports the pages asMEM_MAPPED).

-

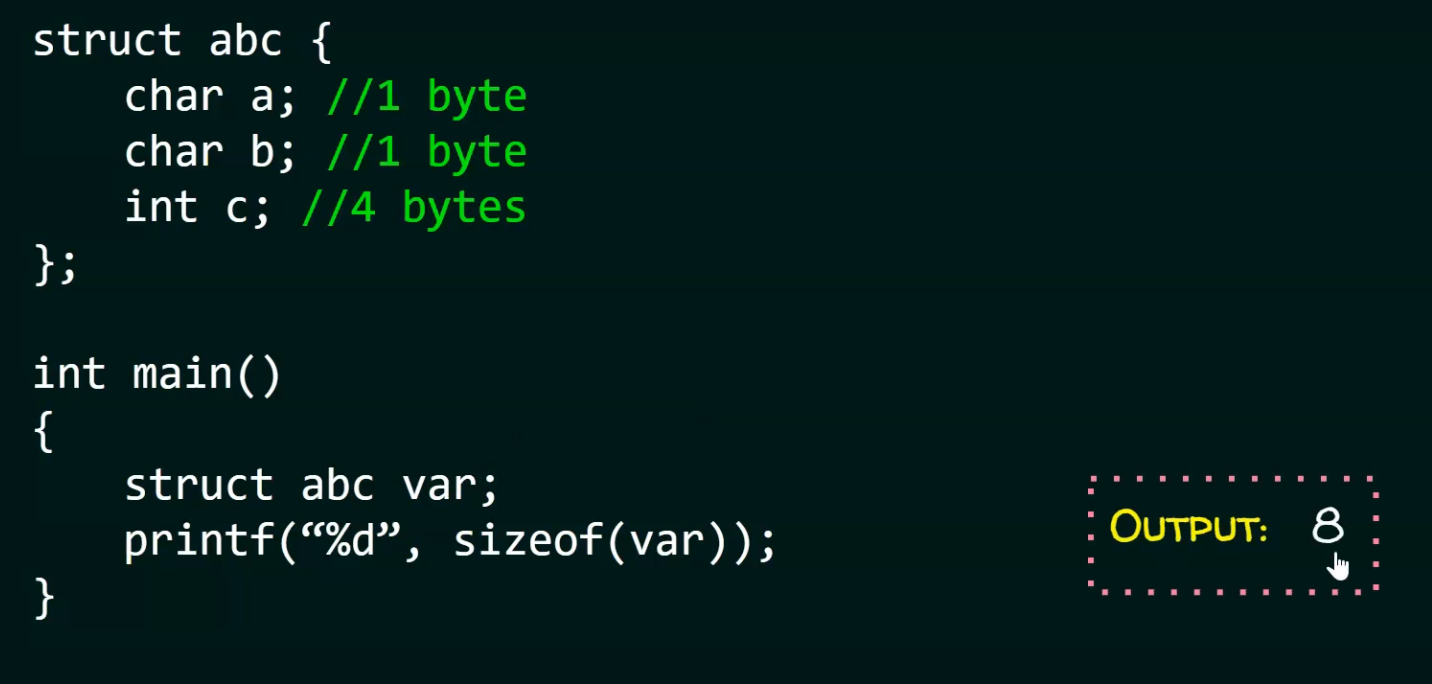

Task Manager (Windows)

-

Task Manager only let's you see "private bytes", which is data that is private to the process.

-

The 'Details' section allows to view a bit more information, if right clicked on the table.

-

Process Explorer (Windows)

-

Similar to VMMap.

-

I don't know which is better, probably this one if I were to guess.

~VMMap (Windows)

-

Impressions :

-

(2025-11-18)

-

Really basic. It doesn't give much, as it's really old.

-

Basic but confusing, idk.

-

-

VMMap .

-

Is a Windows GUI tool from Microsoft Sysinternals that visualizes a process’s virtual memory layout and usage. It breaks memory down by type (Private, Image, Mapped File, Heap, Stack, etc.), shows committed vs reserved, identifies owning modules, and lets you take/compare snapshots.

-

Windows only. On Linux/macOS use tools like

pmap/smaps,proc/vm_stat,perf, or process-specific profilers. -

Run

VMMap.exeas Administrator for full information.

WinDbg (Windows)

-

Advanced stack/heap debugging for Windows binaries.

!heap -s # Show heap summary

!address # Memory layout overview

-

Demo .

Get-Process (Windows)

-

Use on Powershell.

-

Thread count and stacks

-

Just replace

<pid>.

Get-Process -Id <pid> | Format-List Id,ProcessName,WorkingSet64,PrivateMemorySize64,VirtualMemorySize64,@{Name='Threads';Expression={$_.Threads.Count}} -

-

List loaded modules (may hint at large static data).

-

Just replace

<pid>.

(Get-Process -Id <pid>).Modules | Select ModuleName,FileName,@{n='FileSizeMB';e={[math]::Round(($_.ModuleMemorySize/1MB),2)}} | Sort-Object FileSizeMB -Descending | Format-Table -AutoSize -

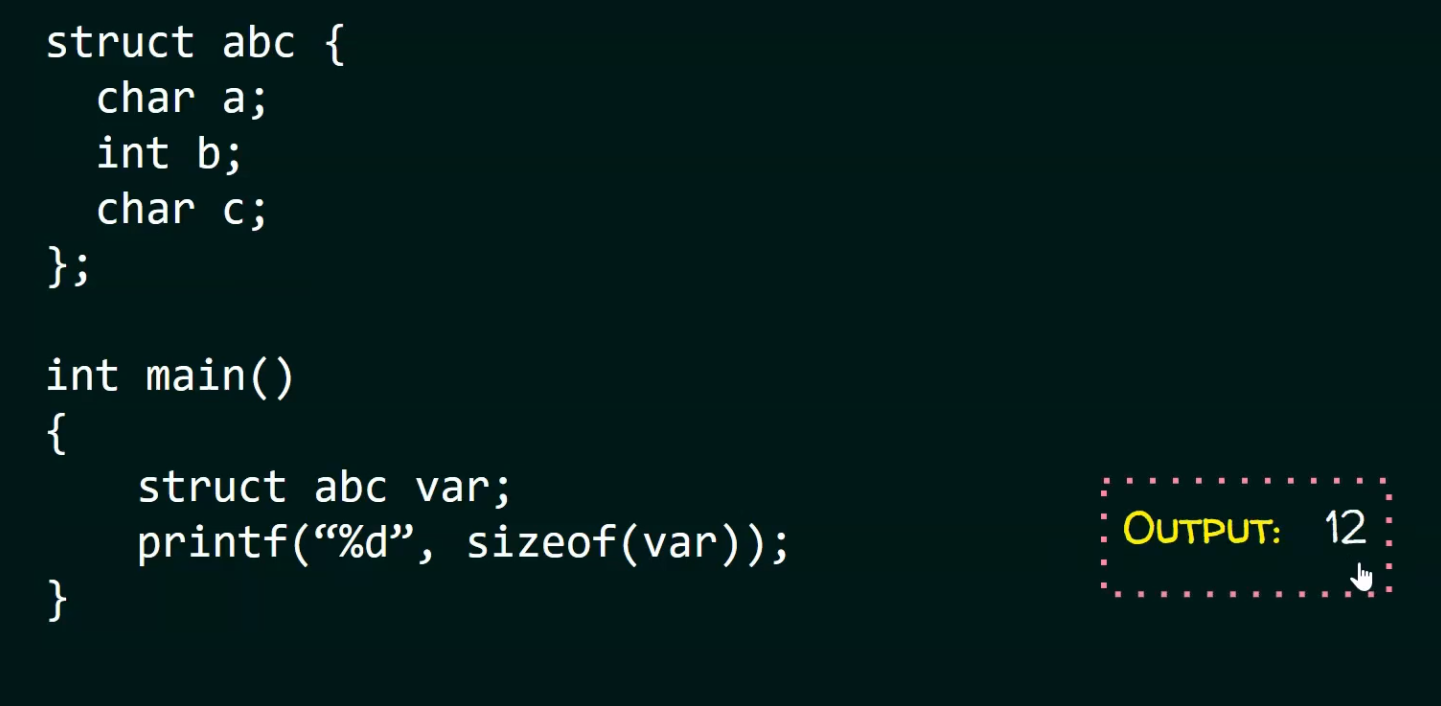

Memory Alignment

Why to align

-

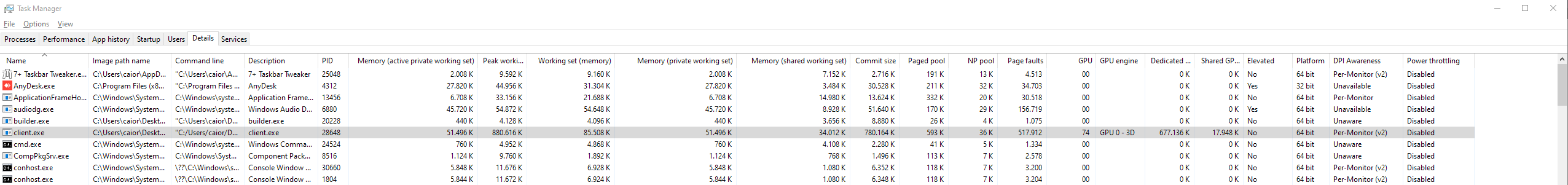

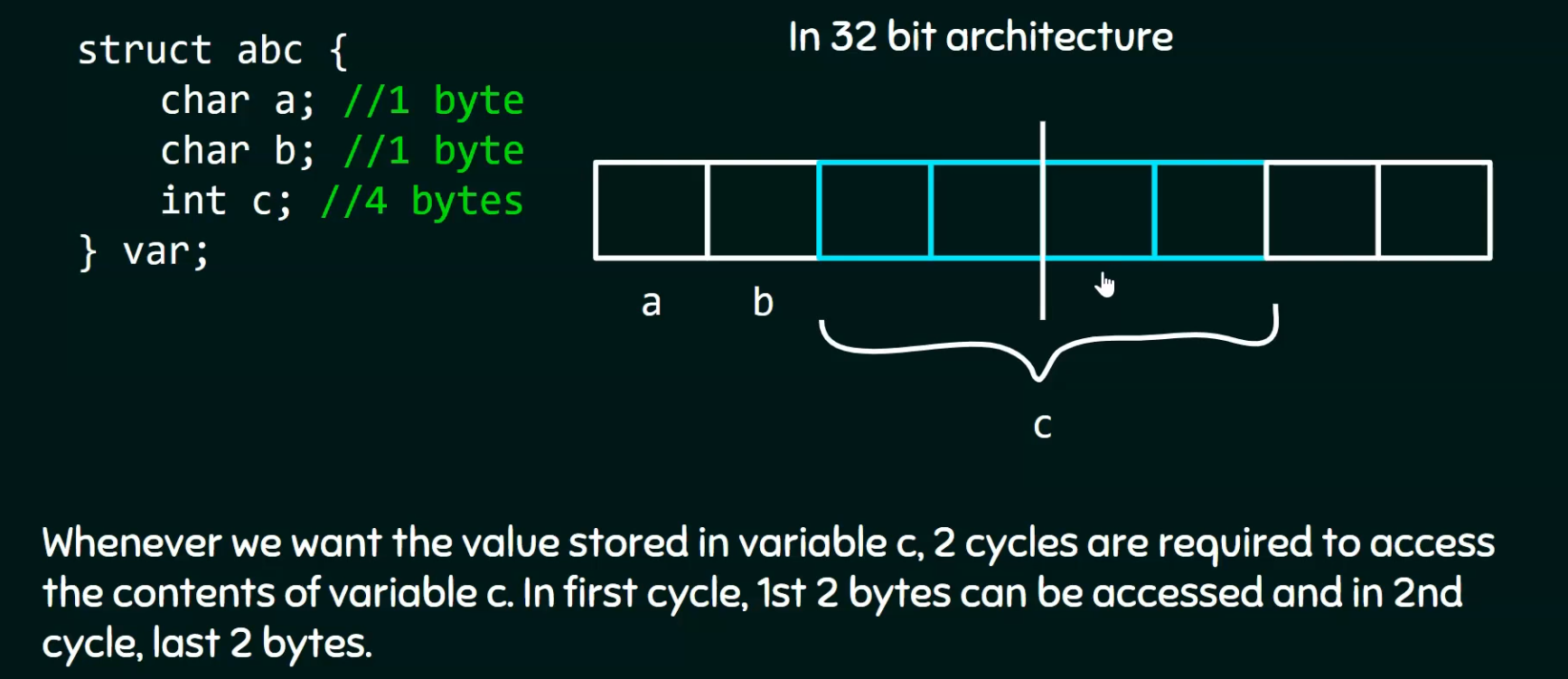

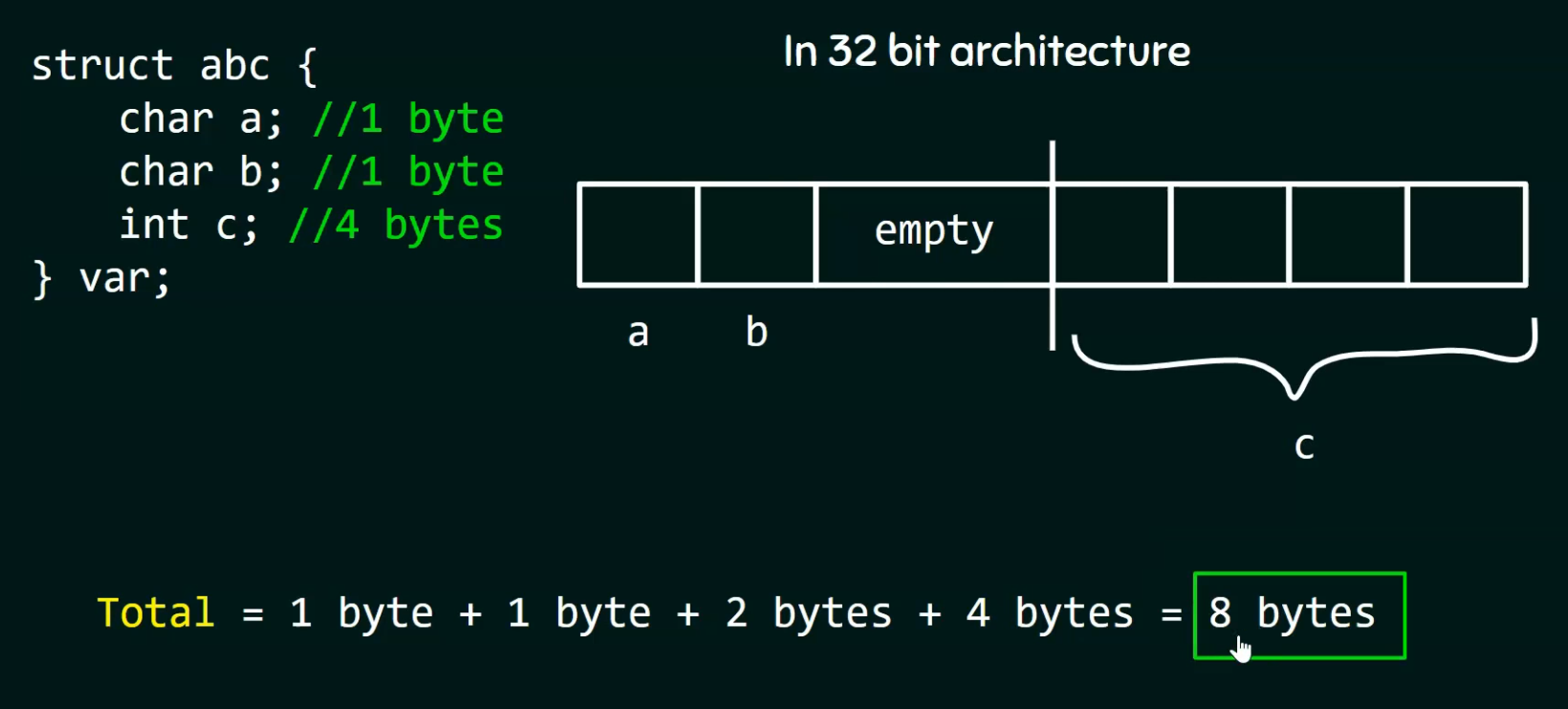

The scenario below causes unnecessary wastage of CPU cycles.

-

.

.

-

If we use padding (empty space) we can improve the CPU cycles, at the cost of the struct storing more memory.

-

.

.

-

.

.

-

The order of the elements matters, as it can introduce more padding than necessary:

-

.

.

-

.

.

Memory Access

-

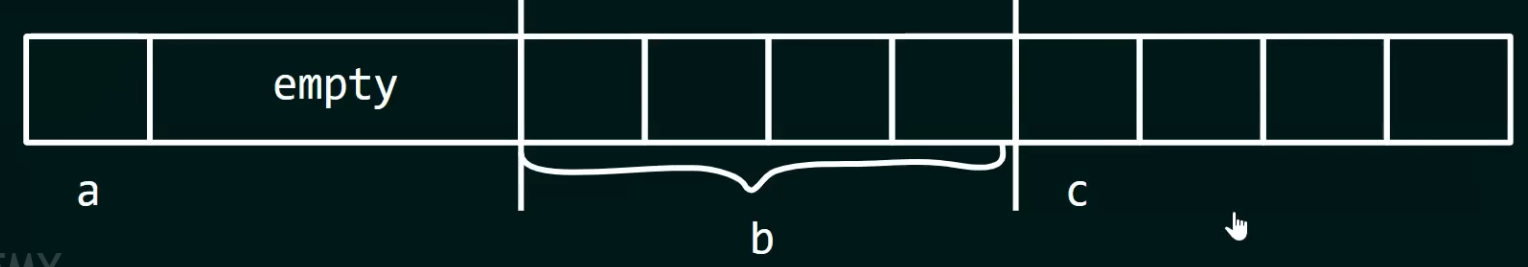

Processors don't read 1 byte at a time from memory.

-

They read 1 word at a time.

-

32-bit Processor :

-

Word size is 4 bytes.

-

-

64-bit Processor :

-

Word size is 8 bytes.

-

Size

-

The total number of bytes that a single element actually occupies in memory, including any internal padding required by alignment.

Offset

-

Defines where a field resides relative to a structure’s base address.

-

Example :

-

In

struct { int a; char b; }, ifastarts at offset0,bmight be at offset4due to alignment padding.

-

Stride

-

Byte distance between consecutive elements in an array or buffer.

-

It’s not “after the element finishes”, it’s the total distance between consecutive starts .

-

That’s why stride includes all bytes (data + padding) in a single element.

-

Example :

-

In a vertex buffer with position (12 bytes) + color (4 bytes), stride = 16 bytes. The next vertex starts 16 bytes after the previous one.

-

Vertex 0 starts at byte

0. -

Vertex 0 occupies bytes

0–15. -

Vertex 1 starts at byte

16.

-

-

Address

Alignment

-

Alignment and Size are different things.

-

Alignment == "Divisible by".

-

Required byte boundary a value must start on, typically a power of two.

-

Hardware or ABI rule ensuring each type begins at addresses divisible by its alignment requirement.

-

.

.

-

An address is said to be aligned to

Nbytes , if the addresses's numeric value is divisible byN. The numberNin this case can be referred to as the alignment boundary . Typically an alignment is a power of two integer value. -

A natural alignment of an object is typically equal to its size. For example a 16 bit integer has a natural alignment of 2 bytes.

Unalignment

-

When an object is not located on its natural alignment boundary, accesses to that object are considered unaligned .

-

Some machines issue a hardware exception , or experience slowdowns when a memory access operation occurs from an unaligned address. Examples of such operations are:

-

SIMD instructions on x86. These instructions require all memory accesses to be on an address that is aligned to 16 bytes.

-

On ARM unaligned loads have an extra cycle penalty.

-

-

If you have an unaligned memory access (on a processor that allows it), the processor will have to read multiple “words”. This means that an unaligned memory access may be much slower than an aligned memory access.

-

This can also lead to undefined behavior if the unaligned memory is within cache bounds.

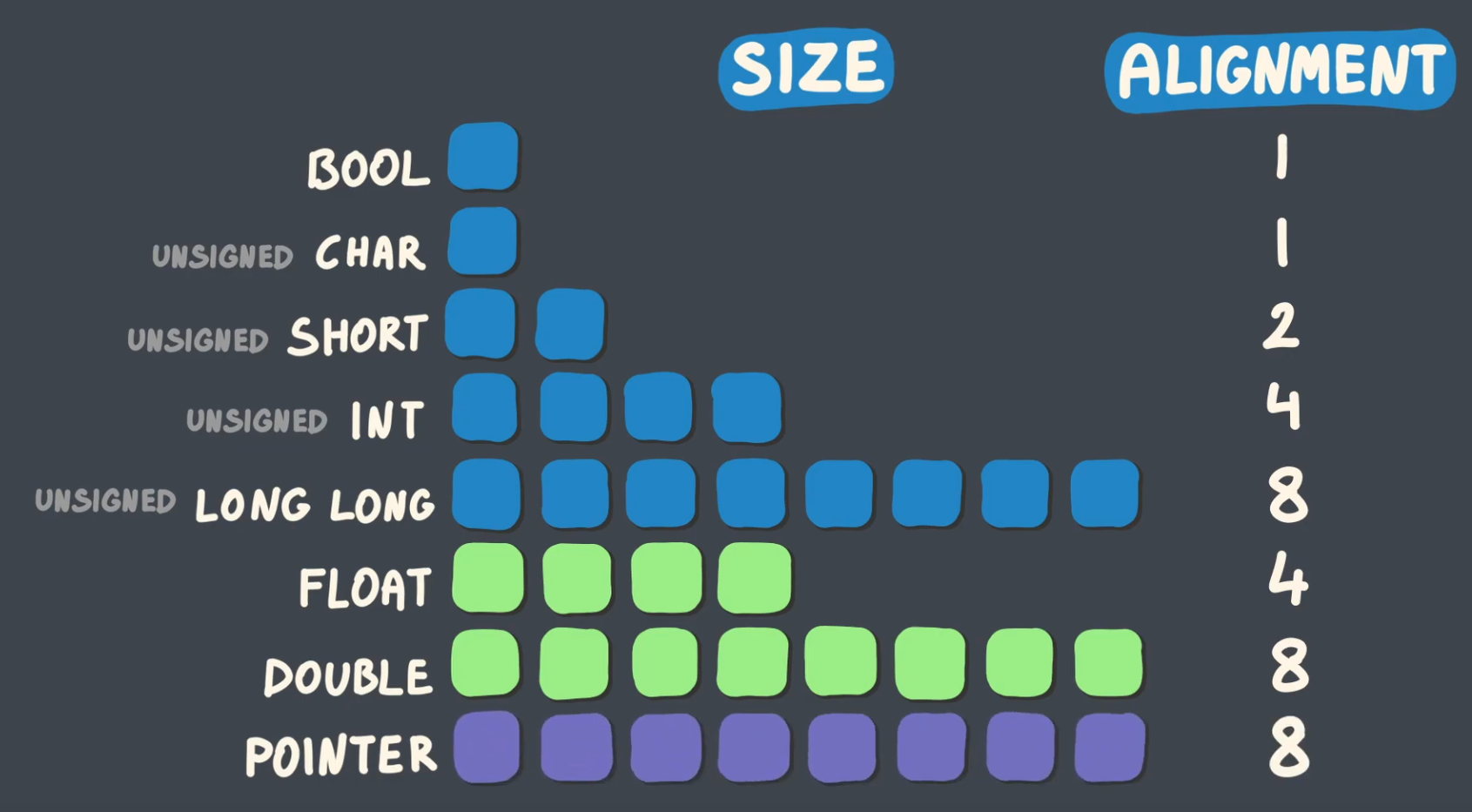

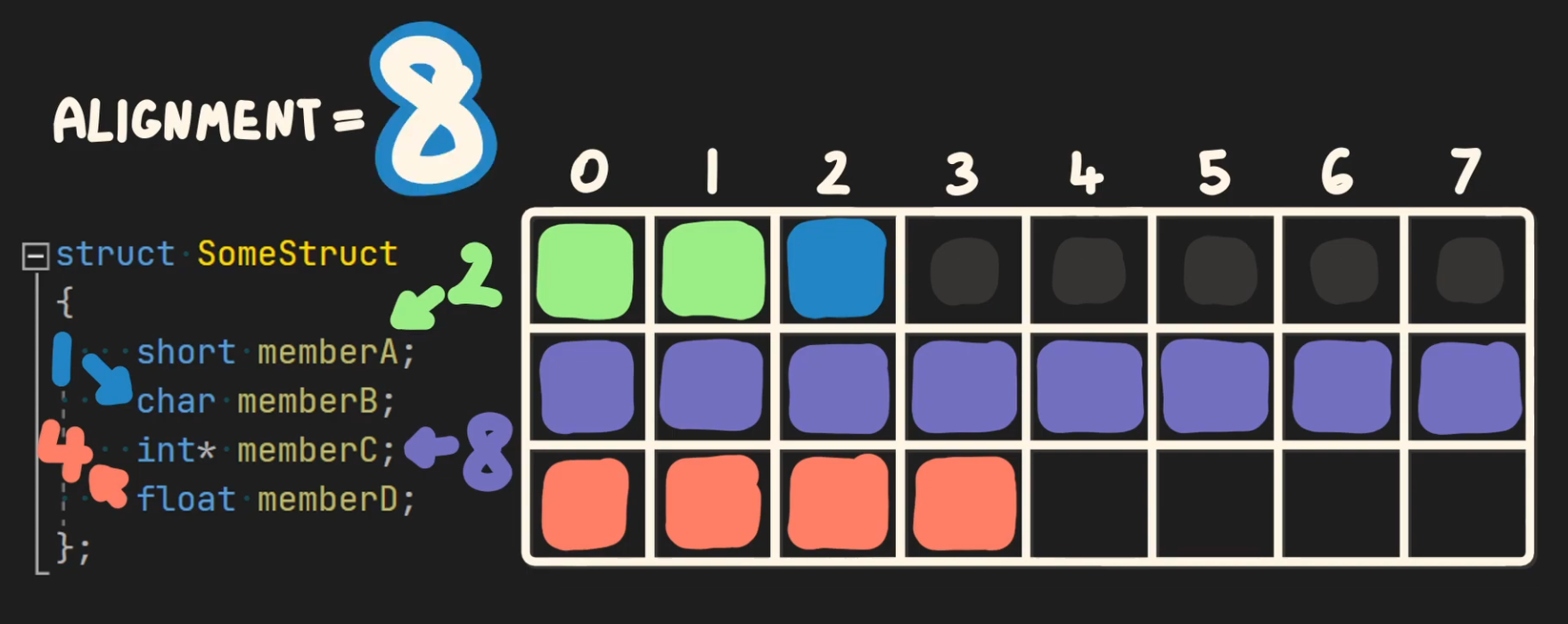

Implicit Alignment

-

When placing a field, the compiler ensures the field's offset is a multiple of the field's alignment. If the current offset is not a multiple of the field's alignment, the compiler inserts padding before the field so the resulting offset becomes a multiple of the alignment.

-

When placing field F the compiler ensures

offset(F) % align(F) == 0. -

If not, it inserts

padding = (align(F) - (offset % align(F))) % align(F)bytes before F. -

The struct’s overall alignment is

max(align(member)). The compiler may add trailing padding sosizeof(struct)is a multiple of that max alignment.

-

-

A struct adds implicit padding between members, based on the alignment of the member with the highest alignment.

-

The gray dots indicate the implicit padding added by the compiler.

-

.

.

-

It may also add padding at the end of the struct, so the struct is divisible by its alignment. This ensures that when the struct is used as an array, each struct will be properly aligned along with its members.

Odin

-

Alignment, Size and the Pointer are related, such as:

-

size_of(T) % align_of(T) == 0. -

uintptr(&t) % align_of(t) == 0. -

Check Odin#Alignment .

-

-

Many operations that allocate memory in this package allow to explicitly specify the alignment of allocated pointers/slices.

-

The default alignment for all operations is specified in a constant

mem.DEFAULT_ALIGNMENT.

std140 and std430

-

Both are GLSL memory alignments.

Allocators

Lifetimes Hierarchy

-

Permanent Allocation :

-

Memory that is never freed until the end of the program. This memory is persistent during the program lifetime.

-

-

Transient Allocation :

-

Memory that has a cycle-based lifetime. This memory only persists for the “cycle” and is freed at the end of this cycle. An example of a cycle could be a frame within a graphical program (e.g. a game) or an update loop.

-

-

Scratch/Temporary Allocation :

-

Short-lived, quick memory that you just want to allocate and forget about. A common case for this is when generating a string and outputting it to a log.

-

Types of Allocators

-

-

There's a lot of things there.

-

-

C#malloc .

Making your own allocator

Where to allocate

Algorithms for searching for free blocks

-

First Fit.

-

Next Fit.

-

Optimization from First Fit, but increases fragmentation, apparently.

-

-

Best Fit.

Coalescing ("Growing together, fusing")

-

When we have two free blocks next to each other, merge them together into one large block.

Strategies

-

On free: coalesce.

-

Coalesce only above and below, once on free.

-

This is preferred as it has a more predictable performance.

-

-

Coalesce once in a while.

-

This can take a little while, but removes the need to do it every operation.

-

-

Free List, Where to allocate a block, Coalescing - Chris Kanich .

-

Exploring a heap allocated memory with

gdb, showing free lists, etc - Chris Kanich .

Tools: Memory Analysis

ASan (Address Sanitizer)

-

Accessing memory outside its scope causes a Segfault, but accessing memory inside another valid region of code can cause memory corruption.

-

Because of this, ASan is used to check if accesses are within the array bounds, etc.

Flags

-

-

"If you run it with

set ASAN_OPTIONS=help=1, it'll dump out a list on startup too."

-

-

Used in Odin:

-

set ASAN_OPTIONS=detect_stack_use_after_return=true:windows_hook_rtl_allocators=true

-

Crash Report: Registers

-

PC (Program Counter) :

-

Also known as the Instruction Pointer (IP) in x86.

-

Points to the next instruction to be executed.

-

In ASan reports, the PC indicates where the crash (e.g., use-after-free, buffer overflow) occurred.

-

-

BP (Base Pointer / Frame Pointer) :

-

Used to track the base of the current stack frame in functions.

-

Helps in unwinding the call stack during debugging.

-

May not always be present (e.g., in optimized builds where frame pointers are omitted).

-

-

SP (Stack Pointer) :

-

Points to the top of the stack.

-

Used for managing function calls, local variables, and return addresses.

-

ASan uses this to detect stack-based buffer overflows or stack-use-after-return.

-

Warnings

-

Failed to use and restart external symbolizer!-

Means that ASan could not use an external tool to convert raw memory addresses into readable file names, line numbers, and function names in your stack trace.

-

Why :

-

Missing Symbolizer Tool

-

ASan relies on an external program (like

llvm-symbolizeroraddr2line) to map addresses to source code locations. -

If this tool is not installed or not in your

PATH, ASan can't resolve symbols properly.

-

-

Incorrect Path or Permissions

-

Even if the symbolizer exists, ASan might fail to execute it due to:

-

Wrong permissions (e.g., no execute access).

-

Anti-virus blocking the tool.

-

-

-

Windows-Specific Issues

-

On Windows, ASan expects

llvm-symbolizer.exeto be available. -

If you're using MSVC, it might not be bundled by default.

-

-

ASan Could Not Restart the Symbolizer

-

If the symbolizer crashes or times out, ASan gives up and shows this warning.

-

-

-

Fix :

-

Install LLVM .

-

-

Valgrind + massif-visualizer

-

"Massif Visualizer is a tool that visualizes massif data. You run your application in Valgrind with

--tool=massifand then open the generatedmassif.out.%pidin the visualizer. Gzip or Bzip2 compressed massif files can also be opened transparently." -

-

Created 16 years ago.

-

Updated 2 weeks ago.

-

-

Tracks heap usage over time and generates memory snapshots.

-

Platforms :

-

Linux

-

Primary platform, best support

-

-

macOS

-

Limited support, works on older versions without Apple Silicon

-

-

Windows-

Not natively supported.

-

-

-

Languages :

-

C

-

Full support.

-

-

C++

-

Full support.

-

-

Odin

-

Partial support, requires debug symbols and manual suppression files.

-

-

Rust

-

Works, but may need

--tool=memcheckfor leaks.

-

-

Other compiled languages

-

Any language that compiles to native code can be analyzed but may need extra configuration.

-

-

-

How to use :

valgrind --tool=massif ./your_program

massif-visualizer massif.out.* # GUI viewer

-

Pros :

-

Shows peak memory usage and allocation trends.

-

rr

+ GDB/LLDB (Time-Travel Debugging)

-

Records execution and lets you rewind to see when memory was freed.

-

How to use :

rr record ./your_program # Records execution

rr replay # Debug with GDB/LLDB

-

Key commands :

watch -l *ptr # Break on UAF access

backtrace # See who freed memory

GDB/LLDB Stack Frames

-

Inspect the call stack and local variables.

-

Key commands :

bt full # Show full backtrace with locals

info locals # List all local variables

Dr. Memory

Handles instead of Pointers

HandleMap or HashMaps?

-

A handle_map_static.

-

A handle is nothing more than an index while using a sparse array.

-

Super lightweight.

-

-

A

map[int]Listener, where each int is a "handle."-

The int could be a random number, maybe obtained via Unix time.

-

-

What’s the difference ?

-

HandleMap:

-

Works really well when the object being stored is a pointer. It’s far safer.

-

Handle somehow requires it to also be stored inside the Listener.

-

-

HashMap:

-

Can be intrinsically lighter on memory.

-

Does not require the object stored in the HandleMap to contain a handle.

-

-

No need to worry about static memory limitations.

-

The HashMap expands automatically.

-

-

-

-

Which to choose :

-

HandleMap for storing pointers; always.

-

HashMap for non-pointers.

-

Articles

-

Handles are the better pointers .

-

The article is very good.

-

It doesn’t show any code, but all concepts are explained and the advantages of the approach are clearly presented.

-

-

-

Important conclusion about OOP and Ownership Semantics (OS):

-

In general, most hard problems cannot be solved at compile time; because of this, adding more and more concepts to the type system of the language will not help without adding extra costs. This does not mean ownership semantics are bad but that they are not a solution for many problems in that domain.

-

A lot of the problems related to responsibility are better solved with forms of “subsystems” within programs which handle groups of “things” and give out handles to the “thing” instead of a direct reference.

-

This is related to the approach many people already use to bypass the borrow checker by using indices/handles.

-

Handles can contain a lot more information than a single number. A common approach is to store a generation number alongside the index in the handle. If a generation has expired, but the handle is used, the subsystem can return a dummy sentinel value and report an error.

-

Other approaches aim to reduce the need for ownership responsibility in the first place. By keeping data structures POD , trivially copyable, and with a useful zero value, you can rethink the problem and simplify code. This places more emphasis on the data and algorithms themselves rather than the relationships between objects and types.

-

-

Final conclusion of the article:

-

The main argument is to demonstrate how OS and OOP both result in a "(linear) value hierarchy of behavior, where the values act as agents."

-

Ownership semantics can be a useful tool for certain problems, but due to their underlying linear logic, they cannot be used to express non-linear problems, which leads people to try to bypass the concept entirely.

-

-

(2025-07-03)

-

I found the article very interesting.

-

I found it interesting how the use of handles was mentioned as something that could solve the problem and how it's used in Rust to work around linearity issues.

-

I don’t yet know the counterarguments to this Rust linearity problem, but if it’s really solved through some kind of handle trick, then it does seem like Rust hasn’t solved an important problem — it just complicates things unnecessarily.

-

-

Libraries

-

-

Very interesting and quite simple as well.

-

From what I saw through ChatGPT, its code follows a very classical handle system structure.

-

Check the README to understand the best usage recommendations, considering virtual memory limitations for the web.

-

Questions :

-

Use of

$HTin the definition of a handle_map.-

See the explanation in the example in Odin#Parametric Polymorphism (Parapoly) .

-

-

-

Usage examples

-

The sokol-gfx API is an example of a C API that uses handles instead of pointers for rendering resource objects (buffers, images, shaders, …):

-

The Oryol Gfx module is a similar 3D API wrapper, but written in C++:

-

The Oryol Animation extension module is a character animation system that keeps all its data in arrays:

Ownership Strategies / Destruction Strategies

-

"Ownership determines destruction strategy. The stronger the ownership, the simpler the destruction should be."

-

The entity always owns the Object. Necessarily the Object should die when the entity dies.

Motivation

Disclaimer

-

This analysis I'm making below is from a challenge I was facing in my Odin engine.

-

It's more of a sketch of what was going on in my head at the time. Some things probably doesn't make much sense, unless in the proper context.

Back to the analysis

-

Annoying places that led me to think about the subject:

-

bodies

-

layers.

-

tweens.

-

~timers

-

if I rework the system.

-

-

world init / world deinit is very easy to forget.

-

The 'struct-based lifetime aggregation' system helped a lot with this.

-

-

-

Post about the subject, focusing on the tween system:

eng.tween( value = &some_vector_inside_an_entity, end = some_vector, duration_s = 0.1, on_end = proc(tween: ^eng.Tween) { // stuff }, )-

This is how I call a tween. The only thing it needs to do for this tween to work is call

eng.tween_system_init()at the beginning of the game,eng.tween_system_deinit()at the end of it, and polleng.tween_system_update(dt)every frame for thetween_systemto process every tween stored when callingeng.tween(..). -

When a tween ends processing, it gets removed automatically by the

eng.tween_system_update(dt). -

The problem is kind of obvious: if the entity dies, the tween has a reference to a pointer inside the entity and the system crashes; UAF.

-

I came up with 5 major ideas to solve this problem, but I'm not really happy with them, or I don't know if they are good practice:

-

1 - The entity stores the tween or a handle to the tween, so when the entity dies, I can manually ask to remove the tween and everything is ok.

-

2 - The tween doesn't store a pointer to some information in the entity, but a handle to it.

-

3 - The

tween_systemdoesn't exist. The entity has a tween stored, and MANUALLY calls a new function calledtween_process(&the_entity_tween)every frame of the entityupdate. The tween doesn't need to be destroyed, as it doesn't own the value pointer. The existence of the tween is tightly linked to the existence of the entity. Just stop callingtween_updateand you won't have a UAF. -

4 - The entity doesn't care about the existence of the tween and can die in peace. The tween knows when the entity died and removes "bad tweens" and never tries to access freed memory. This could be done through:

-

4.1 - The entity has a "pointer to lifetime handle" inside of it. When calling the tween, it passes this handle as an argument for the tween. Every time an object stores this handle, its internal counter goes up by 1. When the entity dies, it changes the handle state to

dead = trueand subtracts 1 from the counter. Theeng.tween_system_update(dt)checks if the handle isdeador not; if so, it frees the "bad tween" and subtracts 1 from the counter. You got the idea. The counter only serves as a way to analyze the memory on game deinit. -

4.2 - The entity has an "event struct". When calling the tween, it passes a pointer to the event so the tween can register a function pointer to be called when the event is emitted; the content inside this function pointer would be the destructor for the tween. When the entity dies, it calls something like

event_emit(the_entity_destructor_event), and every system that subscribed to it will be destroyed. This kinda reminds me a bit of RAII.

-

-

My thoughts on each strategy:

-

1, 2 and 3: 3 is clearly the best in terms of safety, but the problem with all 3 is that it makes the entity aware of the existence of a tween. The tween needs to know how many tweens will be used at the same time beforehand, or use an array that will need to be destructed. This makes the API look less pleasing. So many systems could use a tween and it sucks that it would be just a simple plug-n-play. I wish I could call

tween(..)and be done with it; let thetween_systemhandle the rest. -

4.1 and 4.2: They both sound a bit cheesy. The tween SHOULD die as the entity dies, as it has a pointer to it, but this strategy throws the responsibility to a 3rd party (a lifetime handle or event emitter) to manage the problem. This introduces a level of abstraction that I'm not too fond of.

-

-

Finally, if I were to choose, I'd go for the 4.2 to clean the API, or go back to

3, if it ends up not being a good idea.

-

Ideas

-

The object is stored internally in the Entity :

-

The Object doesn't have to worry about being destroyed, since no one outside the Entity references it .

-

Access is intrinsically tied to the lifetime.

-

'Stateless' seems to be a word that defines this strategy.

-

Examples where I use this :

-

Timer system.

-

Need to advance time manually via

timer_is_finished. -

In that case, I would do

en.tween_update(^Tween, dt).-

The dt is optional, like in the Timer case.

-

-

-

-

For a Tween :

-

The entity has a Tween_System

-

Basically to have an array instead of unitary values.

-

Use a single update.

-

-

The entity has multiple Tweens

-

Requires that I know the maximum number of concurrent tweens I will have at any moment.

-

-

The Tween can still have on_enter and on_end functions, no problem.

-

A Tween can be torn down and rebuilt however you want, so when a tween finishes I can create another tween immediately afterwards using the same Tween.

-

The Tween never needs to be destroyed. It doesn't own anything.

-

-

-

The Object must be destroyed manually during the Entity's destruction :

-

When the Entity is destroyed, it calls the destruction of the Objects it owns.

-

Problems :

-

Compared to "The Object doesn't have to worry about being destroyed, since no one outside the Entity references it":

-

forgetting to update: no big deal.

-

forgetting to destroy: memory leak and UAF.

-

So this technique is less safe.

-

-

-

Examples where I use this :

-

Bodies / Body Wrappers system.

-

This system makes sense, since a Body needs to be destroyed in Jolt anyway, so a destructor call is inevitable.

-

-

-

For a Tween :

-

The entity has a Tween_System

-

Basically to have an array instead of unitary values.

-

Use a single update.

-

-

The entity has multiple Tweens

-

Requires that I know the maximum number of concurrent tweens I will have at any moment.

-

-

eng.tweenreturns a handle to the tween. -

This can be annoying for chaining tweens, having to always have a place to store the tween data.

-

In this case, I could implement a system where tween chaining happens without the need for on_end, via use of

eng.tween_chain, something like that.

-

-

The tween update is done automatically via

eng.tween_update(dt), called directly by the Game Loop, each desired frame. -

Considering that a tween destroys itself automatically when finished, it can be weird to call the destruction of something that's already been destroyed.

-

The tween might not destroy itself automatically, but that makes things a bit more annoying, increasing the verbosity of the tween callback to always destroy itself.proc(tween: ^Tween) { eng.tween_destroy(tween) //or eng.tween_destroy(tween.value) //if using a handle. }-

This changes NOTHING. Explicitly destroying the tween in the callback still requires me to destroy it when destroying the entity. Nothing changes.

-

-

-

-

-

Use of handles :

-

The tween doesn't store a pointer to some information in the entity, but a handle to the information.

-

This means that the entity must have the handle stored, so when the entity dies, the handle is correctly removed.

-

The tween system then tries to tween the data, but when attempting to

getthe information inside the handle, it realizes the handle is now dead and deletes the tween. -

When calling the tween:

-

We need to pass the handle for the data, instead of the data; so no new argument is added.

-

We maybe need to pass the handle_map related to the handle.

-

An alternative is to use a global handle_map.

-

-

-

Disadvantages :

-

I have to store a handle for every pointer I want to tween, which means duplicating the data.

-

I would have a value and a pointer to this value, wrapped around a handle.

-

That's really weird.

-

Another option would be to store the data somewhere else and just have the handle around for the entity, but this could be even weirder.

-

-

A handle_map for

rawptrcould be an annoyance for generic procedures, such as the tween_system.

-

-

About the handle map :

-

The handle_map has the same (or higher) lifetime as the tween system.

-

The handle_map is implicit, without having to pass it around:

-

This means that a generic handle_map would have to be used, storing

rawptr.-

This could be an annoyance for the Tween system, as I wouldn't have many ways of checking if the data for the

valueandendis compatible with each other. -

Overall, it's a bit annoying for generics.

-

-

The handle_map is part of the game.

-

ok.

-

-

The handle_map is global.-

I don't think anything outside the game would want to tween something.

-

-

The handle_map is part of the scene.-

When exiting the scene, the handle_map is cleared.

-

If the handle_map used by the tween_system is exclusively the handle_map of the current scene, that means that we can't tween something during a scene change, as this means that the whole tween_system would be cleared on a scene deinit.

-

-

-

The handle_map is explicit, having to pass it around:-

This increases the argument for calling a tween by one, and also makes the tween store the handle_map, besides the handle.

-

The handle_map could be more specific, but this is not an advantage necessarily, as:

-

Most of the data processed by the tween is different from each other; could be a f32, Vec2, int, etc.

-

-

I don't see this strategy having any real advantage.

-

The handle_map is part of the scene.

-

This would make the most sense, as the only reason for having an explicit handle_map is to have many options for handle_maps.

-

-

-

-

The entity has a handle_map.-

If the entity dies, the handle_map dies as well, crashing the whole system and making the use of the handle pointless.

-

-

-

Advantages :

-

The entity doesn't need to store any tween. We can have any amount of tweens, without any problems.

-

-

Disadvantages :

-

Forgetting to

removethe handle will cause a UAF, as the tween system will be able to access the data that the handle represents.

-

-

-

Game State:-

"Carrying around a

Game_Stateobject which stores all game data so deleting any resource goes through a single place." -

The Game State stores the tweens and the entities.

-

The entity is destroyed through the Game State

game_state_del_entity(gs: ^Game_State, ent: Entity_Id).-

Which will also delete all data associated with that entity.

-

It can remove its tween because it has access to

gs; the entity needs to have an indicator of which tween belongs to the entity either way.

-

-

My thinking:

-

"The entity doesn't own anything"

-

Idk if this is true. When the entity dies some other piece of data MUST die as well.

-

It's a different way to think of ownership. The entity doesn't really own the tween, but the tween must die with the entity; so who owns the data? I mean, I can't say it doesn't have an owner, as that would imply that something like the GameState owns the tween, which isn't true as only destroying the data when deinitializing the Game State would cause a UAF.

-

Seems like the entity and tween are tied together, but if you look the other way around, if a tween dies that doesn't imply that an entity should die.

-

The entity clearly has a higher hierarchy than the tween when it comes to ownership, so I can safely say that the tween belongs to the entity.

-

So, with that in mind, what justifies the tween being out of the entity? What good does it bring to the destruction of the tween?

-

-

Sameness:

-

The entity needs to have a handle for the tween stored or the whole tween itself.

-

Storing only a handle could be a little more problematic if the tween is not killed once the entity dies; but yet, that depends on how the fetch for the tweens is made in the

game_state_tweens :: proc(gs: Game_State) -> []Tween.

-

-

-

Possible advantages:

-

Forgetting to clean up a tween will not cause a UAF, as the entity stored the tween and will take the tween with it when dying.

-

This could cause a memory leak if the tween allocates memory in heap and we forget to clean it up, but it will not cause a crash.

-

THO, this is only possible due to the system being stateless.

-

This is also true for other strategies that store the tween inside the entity.

-

-

-

Possible disadvantages:

-

Same disadvantages of other strategies that have to store the tween or a handle to the tween in the entity:

-

I need to know how many tweens I'll have upfront.

-

The call for a tween could be problematic. If I call a new tween using the same tween_handle or the same tween, while the tween is being used for some other tweening, then this could fail somehow; I would have to overwrite what I asked the tween to do, or just fail the call altogether and say it couldn't be made; this is terrible as it introduces error handling in a simple system.

-

-

Being stateless means that every frame is necessary to fetch all tweens from everywhere in the system, to finally update each one of them.

-

This is a problem when you consider that a tween could be anywhere, not only inside entities.

-

It could be a mess to look up these tweens.

-

-

-

-

Finally:

-

The entity still needs to store a reference to the tween, while also the entity needs to know upfront how many tweens it will use, etc.

-

Even though your strategy could be used, it falls within the realm of the strategies 1 and 3 . I'm looking for a way that the entity doesn't care about the tweening. The tween could live in a general global space, being created freely, BUT still having its lifetime tied to the lifetime of a pointer the tween holds.

-

-

Some people tried to defend the strategy, but I still thought it was garbage and it doesn't deserve to be considered. It doesn't solve anything, keeps the problems of having to store the tweens internally and complicates the whole memory system a lot.

-

-

-

The Object is stored in a global system:-

Problems :

-

ANY pointer is a problematic pointer, since the lifetime of the pointer will always be shorter than the lifetime of the tween system. This requires extra ways to destroy the tween before the pointer stored inside the tween is used.

-

-

Use of Events to destroy Objects :

-

The main characteristic of this system is that the destructor can be defined right when creating the Object, so you know when it will be destroyed; that is, when the event is emitted.

-

For tweens :

-

Why I stopped using this for tweens :

-

I had big lifetime problems across the whole game in the past, but after removing global variables this problem was greatly reduced, diminishing the arguments in favor of using events.

-

An internal system greatly reduces the complexity of the problem, making it much easier to read and understand what's happening.

-

The existence of a destructor for a tween is strange. The tween destroys itself on completion, causing the "destructor" not to be called in 99% of cases . In the vast majority of cases, event listeners were registered in the destructor and unregistered without ever being used.

-

The destructor was just an anti-crash system; its purpose was only to handle an exception where tweens still existed while the pointer of their custom_data no longer existed.

-

-

-

After doing :

// tween() eng.tween( destructor = &personagem.destructor, value = &personagem.arm3.pos_world, end = arm_relative_target_trans_arm3.pos, duration_s = 0.1, custom_data = personagem, on_end = proc(tween: ^eng.Tween) { personagem := cast(^Personagem_User)tween.custom_data personagem.arm3.is_stepping = false } ) // Internal to tween() ok: bool tween.destructor_handle, ok = event_add_listener(destructor, wrap_procedure(tween_delete), rawptr(value)) if !ok { log.errorf("%v(%v): Failed to add event listener.", loc.procedure, loc.line) return nil }

-

-

-

Use of an external Lifetimes Manager system :

-

Use a Lifetime_Handle as an indicator if the entity was destroyed.

-

Each of the individual object systems checks that Lifetime_Handle and will destroy the Object if it notices that the handle was marked as

dead. -

The check must be done in a loop; normally in the object's system loop.

-

This means it is intrinsically a polling system.

-

Problems :

-

If the polling is not done, then the entity will never be destroyed.

-

This is a problem that happens every time the game closes: the Lifetime_Handle is marked as dead, but no final polling is done to destroy the objects.

-

This can cause memory leaks.

-

Although the Lifetime_Handles system can clean up the memory of each indicated thing, this system doesn't have enough information about how the destruction of each element should be performed. Besides, of course, that would be a pain to implement.

-

-

-

-

-

Improvements Applied

Stage 1: Clarity in the definition of lifetimes

-

"Grouped element thinking and systems (n+1)".

-

"struct-based lifetime aggregation".

-

It was the solution I used.

-

-

Ideally I don't want to have any data stored in the global scope, except if .

-

All data should belong to a struct that represents its lifetime.

-

What does this help with?

-

It gets closer to n+1

-

Helps not to forget about initializations and deinitalizations.

-

Makes some lifetimes explicit, making it harder to make UAF mistakes.

-

Makes it much easier to use arena allocators for those objects with the same lifetime.

-

I think it also makes explicit what has a 1-frame lifetime, for use in the temp allocator or another custom arena allocator.

-

This can be very useful when dealing with a low-level render API.

-

Overall: it seems to be an improvement in code clarity and quality.

-

-

Does this help the tween/external systems in any way?

-

I don't think so.

-

The storage of the data is done using another allocator, regardless.

-

The data stored in the system cannot use the same allocator as the entity, since the system should not die when the entity dies.

-

-

Post-change impressions :

-

The system helps to visualize improper access problems, that's all.

-

In a nutshell, it's a way to stay aware of grouped lifetimes, it's "grouped thinking".

-

Therefore it's ok, even if it might not be the best way to visualize/handle the problem.

-

Stage 2: Purity of functions, via removal of global variables and global structs

-

The answer about lifetimes lies in the absence of global variables or global structs.

-

Why I came up with this idea :

-

When the lifetime of something ends, I wanted it to be impossible to access it.

-

This reminded me of Scopes, which do exactly that.

-

-

Notable improvements :

-

Multithreading is safer.

-

The net_connections thread doesn't have access to the game thread's content, since the game is on the worker_game stack.

-

This is the only big advantage in the separation between

globalandgame.-

There's also a gain in function purity, of course.

-

If the game didn't have one dedicated network thread, then

gamewould be basically aglobal. -

Even if

gameis a global variable (like in the crypted core) I would still pass the variable as a function parameter (for sure), for purity, helping to clarify what the function uses.

-

-

-

I liked the solution for RPCs and Jobs, surprisingly.

-

The only thing done is passing the game as an extra arg in the context, via

context.user_ptr; that's it. -

Simple, easy to understand, without requiring changes to the RPC or Job code.

-

If it weren't for that, I would have to pass the game as a procedure arg, having to modify the RPC and Job code accordingly.

-

-

-

Strategies for handling short lived memory

-

The libraries do internal free.

-

Using arenas with scope guard :

-

Shrinks itself:

-

When to shrink :

-

Shrinks itself no matter what.

-

More akin to something stack-based.

-

-

Shrinks itself if a condition is met, where it makes sense to free the memory; too much garbage was accumulated.

-

Not stack-based.

-

-

-

Free last Memory Block from

vmem.Arena -> .Growingwithvmem.Arena_Temp-

Seems to shrinks it self, just like the

runtime.DEFAULT_TEMP_ALLOCATOR_TEMP_GUARD.-

Tests :

-

arena_free_all()-

Correctly shrinks the arena.

-

-

ARENA_TEMP_GUARD()-

When wrapping the

model_creates with this guard, the memory seems to have the same behavior asarena_free_all: spikes to 500mb, then reduce to 140~150mb after 3 secs.

-

-

-

-

Seems much cleaner than the

runtime.DEFAULT_TEMP_ALLOCATOR_TEMP_GUARD. -

I'm unsure about the call to

release; seemed odd to me ON WINDOWS.-

Linux seems ok and intuitive.

-

-

-

Free last Memory Block from

context.temp_allocatorwithruntime.DEFAULT_TEMP_ALLOCATOR_TEMP_GUARD-

IF used with

runtime.DEFAULT_TEMP_ALLOCATOR_TEMP_GUARD, thecontext.temp_allocatorcan shrink it self, apparently.-

Tests :

-

runtime.DEFAULT_TEMP_ALLOCATOR_TEMP_GUARD.-

Careful!! :

-

If the

context.temp_allocatoris wrapped with some other thing (tracking allocator or Tracy), then the guard is not going to begin.-

The condition

context.temp_allocator.data == &global_default_temp_allocator_datafails.

-

-

-

-

-

-

~It seems kinda weird tho, as the

Memory_Blocks are backed by thecontext.allocator.-

The memory blocks can be backed by a different allocator (currently I'm using the

_general_alloc, which is just a more explicit version of thecontext.allocator)

-

-

Thoughts :

-

Not a fan of this, as its behavior is really implicit with

context.temp_allocator, but..... every core lib uses this, so.... aaaaaa....

-

-

-

Rollback the offset fromvmem.Arena -> .Staticwithvmem.arena_static_reset_to+ shrink if a condition is met.-

I would have to implement a guard with this, so I can store the offset I have to rollback, just like

mem.Arena_Temp_Memory. -

When calling

vmem.arena_static_reset_to, shrink if the condition is met.-

Greater than the minimum size, and

reserved - usedis greater or equal tosqrt(reserved); something like this.

-

-

This seems to be reaaally similar to a

vmem.Arena -> Growing.

-

-

mem.Arena_Temp_Memory(Rollback the original Arena offset) + shrink if a condition is met.-

When calling

mem.end_arena_temp_memory, shrink if the condition is met.-

Greater than the minimum size, and

reserved - usedis greater or equal tosqrt(reserved); something like this.

-

-

I wouldn't use this one directly, as I'm using

vmem.Arena, notmem.Arena. -

This seems to be reaaally similar to a

mem.Dynamic_Arena, I think.

-

-

-

Doesn't shrink itself:

-

Rollback the offset from

vmem.Arena -> .Staticwithvmem.arena_static_reset_to.-

It doesn't shrink itself automatically on rollback.

-

I would have to implement a guard with this, so I can store the offset I have to rollback, just like

mem.Arena_Temp_Memory. -

Starts to seem like a stack.

-

-

~

mem.Arena_Temp_Memory(Rollback the original Arena offset)-

It doesn't shrink itself automatically on rollback.

-

The

vmem.arena_static_reset_toforvmem.Arenaseems more convenient. -

Starts to seem like a stack.

-

-

-

Characteristics :

-

The user doesn't control the deallocations.

-

More akin to something stack-based:

-

This strategy would place more guard s internally, so this would enforce something more similar to a stack-based memory.

-

-

-

-

~General allocator, manually freeing after every alloc.

-

This doesn't seem compatible with the concept of "temp" or "garbage".

-

This is useful for something that lives for a undetermined amount of time, or not even in this case.

-

Even if spawning entities and deleting entities, an optimized arena could be used...

-

-

context.allocator.

-

-

-

The libraries don't do internal free.

-

Using arenas with a scope guard :

-

Same options as 'Scope thing internal'.

-

Characteristics :

-

The user controls the deallocation.

-

guard s are only placed by the user, not internally by libraries.

-

-

When the user has access to the deallocation, it might be "too late", as we had the memory spike either way, as there was just too much garbage to clean up.

-

The only way to optimize this is if the user deconstructs the library implementation and places the guard in the places it sees a best fit.

-

-

Not stack-based.

-

Memory keeps existing until ending the guard , not after the stack scope of something internal is ended.

-

"Memory that doesn't make sense to exist, keeps existing until removed by the user".-

This statement actually doesn't make sense as the scope is defined by the guard , and not by the stack scope of the functions.

-

-

-

-

-

Using arenas without a scope guard :

-

Characteristics :

-

Free arbitrary.

-

The user chooses when to free the memory.

-

When the user has access to the deallocation, it might be "too late", as we had the memory spike either way, as there was just too much garbage to clean up.

-

The only way to optimize this is if the user deconstructs the library implementation and frees the arena in the places it sees a best fit.

-

-

-

_temp_alloc-

It's just my version of the

context.temp_allocator, acting explicitly, instead of implicitly through thecontextsystem. -

This fights against all libraries that uses the

context.temp_allocatorimplicitly, as both arenas would be doing the same thing; it's ugly.

-

-

context.temp_allocator.-

It doesn't shrink it self.

-

Huge spike because of this.

-

-

-

Garbage Collection

Automatic Reference Counting (ARC)

-

The object has a field that represents the object's count.

-

Expensive.

-

There are checks every time the object is modified.

-

Cycles are problematic.

Mark and Sweep

-

Has no problems with cycles.

-

There's no need to check every time the object is modified, but the checks are done during the GC Pause, which is where the GC pauses the app to look for garbage.

Initialization

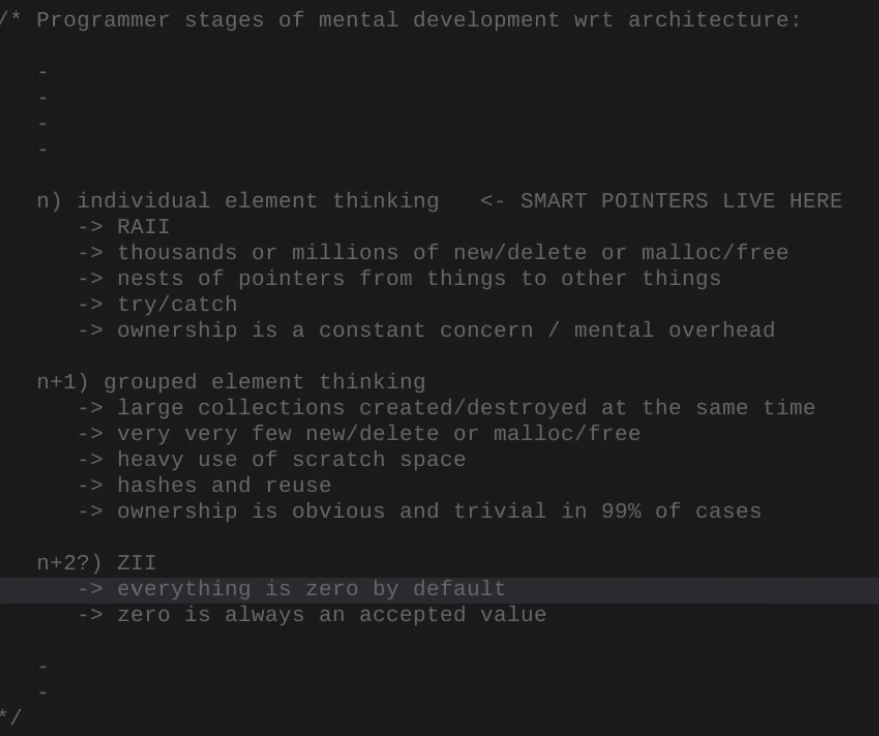

Strategies (n)

-

RAII.

-

Smart Pointers.

-

new/delete malloc/free.

-

try/catch.

-

Rust borrow checker.

Strategies (n+1) (Grouped element thinking and systems)

-

The entity has a block allocator, where all memory used by the entity uses that block allocator.

-

Sounds nice, but doesn't seem to solve the problem of memory being used in other systems.

-

-

Every frame has an arena allocator. Everything that should exist for a single frame uses that allocator.

-

Casey and Jon use this.

-

-

Use PEAK memory to know what size the block should have.

-

Very interesting.

-

Strategies (n+2)

-

ZII and Stubs as alternative ways of memory structure and error handling.

-

Casey about Stubs:

-

Stubs are just a block of zeroes.

-

"If you failed to push something into the arena, you just get a Stub back, it's all zeroed".

-

"When something comes back, just produces a Stub instead of something real, and everything still works".

-

The code doesn't check if the struct is a Stub. The code just assumes the data is something you can use and uses it.

-

For example, when using a 0 Handle, I don't return null, I just return a zeroed entity.

-

-

Stubs :

-

Stubs are minimal or fake implementations of functions, classes or modules, used mainly for testing, incremental development or simulating external dependencies.

#include <iostream> // Real function not yet implemented, we use a temporary stub int calcularImposto(float salario) { std::cout << "[STUB] Function not yet implemented." << std::endl; return 0; // Returns a fixed value to continue development } int main() { float salario = 5000; int imposto = calcularImposto(salario); std::cout << "Calculated tax: " << imposto << std::endl; return 0; } -

ZII (Zero Initialization Is Initialization)

Comparing to RAII

-

Unlike RAII, ZII does not inherently imply resource ownership or cleanup in the destructor.

-

It's about safe default values , not lifecycle management.

-

Both are part of the broader design goal of:

-

Avoiding uninitialized or unsafe state.

-

Ensuring predictable object behavior starting at construction.

-

-

Because of this shared initialization focus , they're often discussed together in contexts like:

-

C++ safety idioms.

-

Codebases transitioning from C-style to C++.

-

Embedded/safety-critical environments.

-

-

Their conceptual scopes differ, but they both leverage constructors to achieve safety and predictability, hence the mental association.

About

-

ZII is true by default for every system.

-

The way you program is by letting zero always be an acceptable value.

-

ZII is a principle that defends that variables be initialized to zero or default values as soon as they are created. This reduces the risk of accessing undefined values.

-

Main characteristics :

-

Prevents undefined behavior when accessing uninitialized variables.

-

Applicable mainly to primitive types and arrays.

-

Avoids hard-to-debug errors.

-

-

Advantages of ZII :

-

Reduces errors related to uninitialized values.

-

Ensures predictability in program behavior.

-

Useful for data structures and dynamically allocated memory.

-

Examples

#include <iostream>

class Example {

public:

int x = 0; // Zero initialization

double y = 0.0;

};

int main() {

Example e;

std::cout << "x: " << e.x << ", y: " << e.y << std::endl;

return 0;

}

int arr[10] = {}; // All elements are initialized to 0

RAII (Resource Acquisition Is Initialization)

About and Meaning

-

Bjarne Stroustrup - "RAII is the best thing the language has" .

-

"Constructors and Destructors pairs is the best feature implemented in the language".

-

"Sometimes this comes out in the name of RAII".

-

"Not the greatest name I've ever heard".

-

-

-

The phrase “Resource Acquisition Is Initialization” emphasizes that:

-

Acquiring a resource happens at the same time the object is initialized (constructed).

-

This ties the resource's lifetime to the object’s lifetime.

-

-

Why Destruction Is Implied :

-

Although destruction is not named, it's implied by C++'s object lifetime rules :

-

If the resource is acquired during initialization, and the object controls the resource.

-

Then releasing it must naturally occur when the object is destroyed.

-

-

C++ deterministic destruction ensures that destructors are called at the end of scope, enabling automatic cleanup.

-

-

Therefore, RAII relies on both construction and destruction, even if the name only mentions the construction side.

Principles

-

Associates resource acquisition (like memory, file handles, mutexes, etc.) with the construction of an object, and resource release with its destruction .

-

Scope-Based Lifetime :

-

In C++, objects declared with automatic storage duration (i.e., local stack variables) are automatically destroyed when they go out of scope.

-

-

Destructor Role :

-

The destructor is the mechanism used to release resources. Since C++ guarantees that destructors of local objects are called when the scope exits (either normally or via exception), this ensures deterministic cleanup.

-

-

Why it "implies" a destructor :

-

For RAII to work, a resource-managing object must reliably release its resource.

-

C++ destructors are guaranteed to be called when the object’s scope ends.

-

Therefore, RAII relies on this guarantee, and the destructor becomes the point where the resource is released.

-

Examples

-

Demonstration of RAII in

unique_ptrandmutex_guard.-

It's all about scope.

-

Exiting the scope calls a function automatically.

-

That's it.

-

#include <iostream>

#include <fstream>

class FileHandler {

private:

std::ofstream file;

public:

FileHandler(const std::string& filename) {

file.open(filename);

if (!file.is_open()) {

throw std::runtime_error("Failed to open the file.");

}

}

~FileHandler() {

file.close();

}

void write(const std::string& text) {

file << text << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

try {

FileHandler fh("test.txt");

fh.write("RAII ensures the file is closed.");

} catch (const std::exception& e) {

std::cerr << e.what() << std::endl;

}

// The FileHandler destructor closes the file automatically.

return 0;

}

Negative points

-

RAII in C++ and comparison with Odin .

-

Odin is soooo much better, wow.

-

-

Makes you allocate and deallocate simple things individually.

-

Sometimes you want to be explicit about things and just free a bunch of things at once.

-

In C++ that would require you to not use the language as it was intended in some ways.

-

In C++ you have to accept the complexity of RAII.

-

-

-

Automatic destructors make you think about failure and error handling in a bad way.

-

Unwinding the object through a destructor is not going to make the error go away. The error needs to be handled depending on the circumstance.

-

You need to think about failures and program around it.

-

In RAII you spend a lot of time writing code to handle failures that will never happen, but the same errors blow up.

-

RAII doesn't solve the problem they needed to solve.

-

Some people criticized his quote, for not making a distinction between RAII and error handling.

-

.

.