Memory

-

Memory .

Lifetime and Ownership

-

Ownership determines whose responsibility it is to free the memory referenced by the pointer, and lifetime determines the point at which the memory becomes inaccessible.

-

It is the Zig programmer's responsibility to ensure that a pointer is not accessed when the memory pointed to is no longer available.

-

Note that a slice is a form of pointer, in that it references other memory.

-

Conventions :

-

In general, when a function returns a pointer, the documentation for the function should explain who "owns" the pointer. This concept helps the programmer decide when it is appropriate, if ever, to free the pointer.

-

For example, the function's documentation may say "caller owns the returned memory", in which case the code that calls the function must have a plan for when to free that memory.

-

Probably in this situation, the function will accept an

Allocatorparameter. -

The API documentation for functions and data structures should take great care to explain the ownership and lifetime semantics of pointers.

-

-

Defer

Defer

-

Defer is used to execute a statement upon exiting the current block.

-

When there are multiple defers in a single block, they are executed in reverse order.

const expect = @import("std").testing.expect;

test "defer" {

var x: i16 = 5;

{

defer x += 2;

try expect(x == 5); // first the test runs, then the defer happens.

}

try expect(x == 7);

}

const expect = @import("std").testing.expect;

test "multi defer" {

var x: f32 = 5;

{

defer x += 2; // runs after this one.

defer x /= 2; // runs first.

}

try expect(x == 4.5);

}

const std = @import("std");

const expect = std.testing.expect;

const print = std.debug.print;

test "defer unwinding" {

print("\n", .{});

defer {

print("1 ", .{});

}

defer {

print("2 ", .{});

}

if (false) {

// defers are not run if they are never executed.

defer {

print("3 ", .{});

}

}

}

-

Example of handling Optionals (

?T) :const jsonParsed: ?std.json.Parsed(std.json.Value) = parseJson(allocator, mapa) catch |err| blk: print("\nERROR | LDtkParser: {}, {s}\n", .{err, mapa}); break :blk null; };-

Correct :

defer { if (jsonParsed != null) { jsonParsed.?.deinit(); } // or if (jsonParsed) |jsonParsed_| { defer jsonParsed_.deinit(); } // or, (not sure which is correct) if (jsonParsed) |*jsonParsed_| { defer jsonParsed_.*.deinit(); } }-

The

deferwill happen at the expected moment, performing actions depending on whether the variable is null.

-

-

Incorrect :

if (jsonParsed != null) { defer jsonParsed.?.deinit(); } // or if (jsonParsed) |jsonParsed_| { defer jsonParsed_.deinit(); } // or, (not sure which is correct) if (jsonParsed) |*jsonParsed_| { defer jsonParsed_.*.deinit(); }-

All syntaxes are valid, but the

deferwill run as soon as theifscope exits, i.e., immediately. Thedeferis executed inside theif, not outside it.

-

-

-

Comparing with Go :

-

Zig's

deferis similar to Go's, with one major difference. -

In Zig, the defer runs at the end of its containing scope.

-

In Go, defer runs at the end of the containing function.

-

Zig's approach is probably less surprising, unless you are a Go developer.

-

errdefer

-

errdeferworks likedefer, but only executes when the function returns with an error inside theerrdefer's block.

var problems: u32 = 98;

fn failingFunction() error{Oops}!void {

return error.Oops;

}

fn failFnCounter() error{Oops}!void {

errdefer problems += 1;

try failingFunction();

}

fn main() !void {

failFnCounter() catch |err| {

return;

};

}

-

Ex1 :

const std = @import("std"); const Allocator = std.mem.Allocator; pub const Game = struct { players: []Player, history: []Move, allocator: Allocator, fn init(allocator: Allocator, player_count: usize) !Game { var players = try allocator.alloc(Player, player_count); errdefer allocator.free(players); // store 10 most recent moves per player var history = try allocator.alloc(Move, player_count * 10); return .{ .players = players, .history = history, .allocator = allocator, }; } fn deinit(game: Game) void { const allocator = game.allocator; allocator.free(game.players); allocator.free(game.history); } };-

Under normal conditions,

playersis allocated ininitand released indeinit. But there's an edge case when the initialization ofhistoryfails. In this case and only this case we need to undo the allocation ofplayers. -

Another notable aspect is that the lifecycle of our two dynamically allocated slices,

playersandhistory, is based on application logic. There's no rule that dictates whendeinitmust be called or who must call it. This is good because it gives arbitrary lifetimes, but bad because we can forget to calldeinitor call it more than once.

-

Comptime

-

"Compile time" is a program's environment while it is being compiled.

-

"Run time" is the environment while the compiled program executes.

-

All compiled languages perform some logic at compile time to analyze code and build symbol tables.

-

Optimizations :

-

Compilers can precompute or inline things at compile time to make the resulting program more efficient.

-

Smart compilers can even unroll loops.

-

Zig makes compile-time execution an integral part of the language.

-

-

Zig has a powerful

comptimefeature to do things at compile time. Compile-time execution can only operate on compile-time known data. Zig providescomptime_intandcomptime_floattypes. Example:var x = 0; while (true) { if (someCondition()) break; x += 2; }-

This won't compile.

x's type is inferred as acomptime_intsince the value0is known at compile time. Acomptime_intmust be aconst. If we change toconst x = 0;we'll get a different error because we try to add 2 to aconst. -

The solution is to explicitly define

xas a runtime integer type:var x: usize = 0;

-

Numeric Literals

-

ALL numeric literals in Zig are of type

comptime_intorcomptime_float. They are arbitrary precision.

const const_int = 12345;

const const_float = 987.654;

-

When assigned to

constidentifiers, we don't need to specify sizes likeu8orf64. -

The values are inserted at compile time. The identifiers

const_intandconst_floatdon't exist in the compiled binary.

Pointers

-

Pointers .

Single-item Pointer (

*T

)

-

Normal pointers in Zig cannot have 0 or null as a value.

-

Setting a

*Tto 0 is detectable illegal behaviour.

-

-

Referencing is

&variable, dereferencing isvariable.*.

const expect = @import("std").testing.expect;

// The function receives a pointer to `u8`.

fn increment(num: *u8) void {

num.* += 1;

// `num.*` accesses the value pointed to by the pointer (dereference).

}

test "pointers" {

var x: u8 = 1;

increment(&x); // Pass a pointer to `x` to `increment`.

try expect(x == 2);

}

-

Sizes :

-

usizeandisizehave the same size as pointers.

test "usize" { try expect(@sizeOf(usize) == @sizeOf(*u8)); try expect(@sizeOf(isize) == @sizeOf(*u8)); } -

-

Coercion / Casting :

-

Pointers are not integers; explicit conversion is needed.

-

-

Recommendations :

-

Prefer slices and array types to raw pointers. Compiler-enforced types are less error-prone than pointer manipulation.

-

Many-item Pointer (

[*]T

)

-

Many pointer types exist to represent what is pointed to: single value or array, known length or not.

-

Most programs need buffers with runtime-known lengths. Many-item pointers represent those.

-

Questions :

-

Example usage confusion:

const expect = @import("std").testing.expect; fn doubleAllManypointer(buffer: [*]u8, byte_count: usize) void { var i: usize = 0; while (i < byte_count) : (i += 1) buffer[i] *= 2; } test "many-item pointers" { var buffer: [100]u8 = [_]u8{1} ** 100; const buffer_ptr: *[100]u8 = &buffer; const buffer_many_ptr: [*]u8 = buffer_ptr; doubleAllManypointer(buffer_many_ptr, buffer.len); for (buffer) |byte| try expect(byte == 2); const first_elem_ptr: *u8 = &buffer_many_ptr[0]; const first_elem_ptr_2: *u8 = @ptrCast(buffer_many_ptr); try expect(first_elem_ptr == first_elem_ptr_2); } -

"Slices can be thought of as many-item pointers (

[*]T) plus a length (usize)."

-

Slices (

[]T

)

-

Slices vs Arrays :

-

Slices do not store data, only a reference to the original array.

-

They store the valid length of the buffer.

-

-

Slices can have runtime variable length; arrays have fixed length known at compile time.

-

-

Slices vs Many-item Pointers :

-

Slices are safer and more convenient.

forloops work on slices.

-

-

Slices are "fat pointers" and are typically twice the size of a normal pointer.

-

Slicing :

-

Create from an array with

x[n..m]. -

Slicing includes

nand excludesm.

const expect = @import("std").testing.expect; fn total(values: []const u8) usize { var soma: usize = 0; for (values) |v| soma += v; return soma; } test "slices" { const array = [_]u8{ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 }; const slice = array[0..3]; // elements 0, 1 and 2. try expect(total(slice) == 6); // returns 6 = 1 + 2 + 3. try expect(@TypeOf(slice) == *const [3]u8); }-

Use

x[n..]to slice to the end.

test "slices 3" { var array = [_]u8{ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 }; var slice = array[0..]; _ = slice; } -

Pointer Types

-

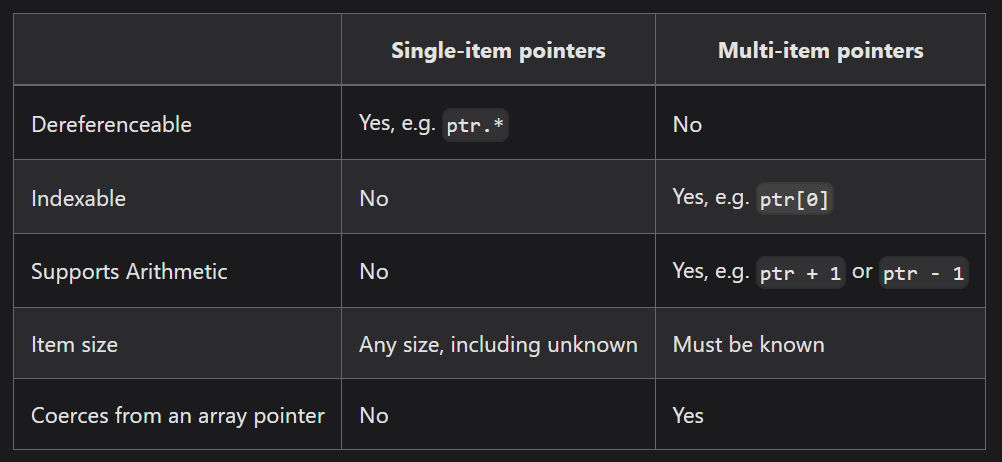

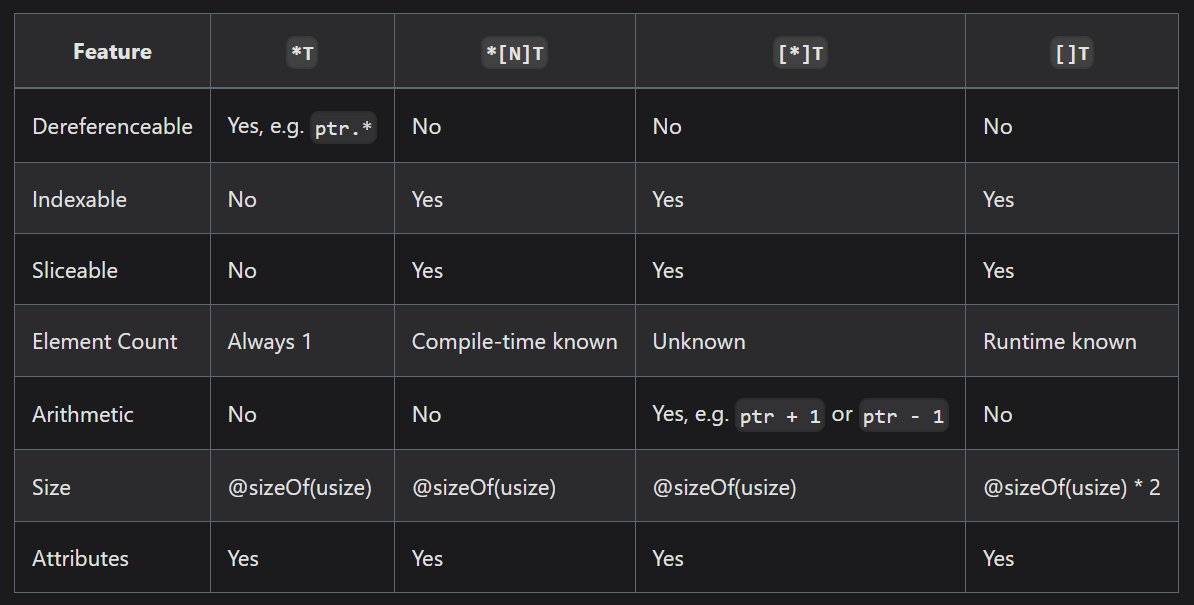

Single-item Pointer vs Multi-item Pointers :

-

.

.

-

-

.

.

-

[]Tis a Slice.

-

Dangling Pointers

-

About :

-

Returning the address of a local.

-

-

Ex1 :

const std = @import("std"); pub fn main() !void { const warning1 = try powerLevel(9000); const warning2 = try powerLevel(10); std.debug.print("{s}\n", .{warning1}); std.debug.print("{s}\n", .{warning2}); } fn powerLevel(over: i32) ![]u8 { var buf: [20]u8 = undefined; return std.fmt.bufPrint(&buf, "over {d}!!!", .{over}); }-

Here we return the address of

buf, butbufceases to exist when the function returns.

-

-

Ex2 :

-

Other examples:

-

Arena allocator created inside a struct, etc.

-

Not fully understood.

-

-

Printing a pointer that pointed to a StringHashMap entry that was removed.

-

A simple, somewhat silly example.

-

-

-

Ex3 :

const std = @import("std"); pub fn main() void { const user1 = User.init(1, 10); const user2 = User.init(2, 20); std.debug.print("User {d} has power of {d}\n", .{user1.id, user1.power}); std.debug.print("User {d} has power of {d}\n", .{user2.id, user2.power}); } pub const User = struct { id: u64, power: i32, fn init(id: u64, power: i32) *User{ var user = User{ .id = id, .power = power, }; return &user; } };-

The problem is

User.initreturns the address of the localuser. That's a dangling pointer. Returning&userreturns an invalid address. -

A simple fix is to change

initto returnUser(not*User) andreturn user;.-

But that's not always possible.

-

Data often must outlive function scope. For that we use the heap.

-

-

-

Ex4 :

fn read() !void { const input = try readUserInput(); return Parser.parse(input); }-

If

Parser.parsereturns a value that referencesinput, that will be a dangling pointer. IdeallyParserwould copyinputif it needs it to live longer. There's nothing here to enforce that. Check documentation or source to know semantics.

-