-

Cool Explanation of Process and Multithread .

-

Uses a bit of machine code to demonstrate common multithreading issues.

-

-

-

He presents everything very well. Great talk.

-

Assumes you already know what mutex, deadlocks, etc., are.

-

It's an intermediate talk, not beginner.

-

Pt2 is very technical for C++, basically explaining a library with techniques.

-

Maybe useful, but not relevant atm.

-

-

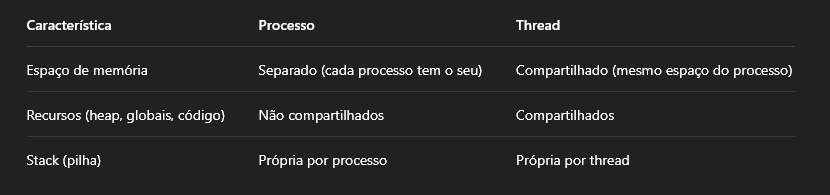

Process vs Threads

-

.

.

-

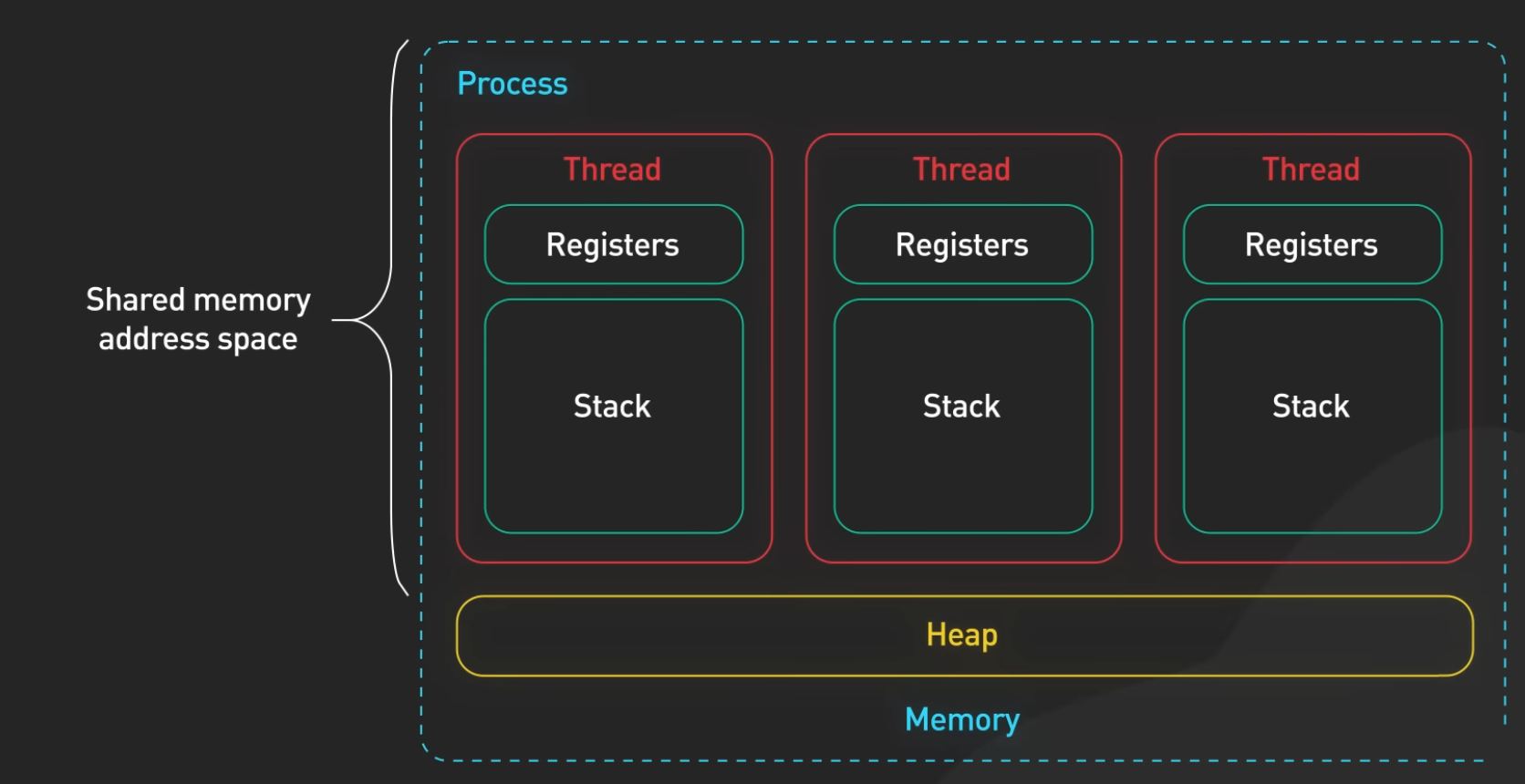

Threads are execution units within the same process.

-

A process can contain multiple threads, all sharing the same process memory space.

-

.

.

-

Memory :

-

All threads (including main) share the same heap, code, and global data, but have independent stacks.

-

Memory shared among all threads :

-

All heap-allocated memory.

-

All memory of global/static variables by the main thread.

-

Main thread stack.

-

Each thread has its own stack. However, pointers to main thread stack variables can be passed to other threads, risking out-of-scope use.

-

Passing a pointer to a local main thread variable to another thread is risky if main exits scope before the other thread finishes.

-

-

-

Multithreading

-

Technique that allows concurrent execution of two or more threads within a single process.

-

Threads can perform tasks independently while sharing process resources.

-

Multithreading is both:

-

A concept (the idea of using multiple threads).

-

A strategy if used directly (e.g., "We use raw threads for parallelism").

-

-

Models :

-

User-Level Threads :

-

Managed by the application, no kernel involvement.

-

-

Kernel-Level Threads :

-

Managed directly by the operating system.

-

-

Hybrid Model :

-

Combines user and kernel threads.

-

-

Main Thread

-

It's the first thread that starts executing when the process is launched.

-

Automatically created by the OS when starting the process.

Resource

-

Something you don't want 2 threads to access simultaneously.

-

Ex:

-

Memory location.

-

File handle.

-

Non-thread safe objects.

-

Starvation

-

~When a thread finishes work much faster than another and ends up doing nothing?

Race conditions

-

When a Resource is accessed by 2 or more threads simultaneously, and at least one of them is a write .

-

Causes Undefined Behavior ; it's critical to avoid this.

Read with concurrent Write

-

"If a thread is modifing a variable and I try only READING this variable on a different thread, what can I expect? I assumed that only 2 thing could happen: I either get the old value, or the new value"

-

More than just “old or new” can be observed in practice. Memory effects include seeing the old value, the new value, a torn (partially-updated) value, or behavior caused by compiler/CPU reordering (stale values, values observed in surprising orders). Which of those can occur depends on alignment/size, hardware cache-coherence, and the language memory model and compiler.

-

atomic single-word writes (aligned to machine word)

-

On most modern CPUs a naturally aligned write of a machine-word-sized integer is atomic at the hardware level — the hardware will not present a half-written word to another core. In that case the reader will typically see either the old value or the new value (once the write becomes visible).

-

Caveat: “typically” is not the same as “guaranteed by the language.” If your language/compiler does not declare the access atomic (e.g., plain

intin C/C++ pre-C11), the compiler may optimize assuming no concurrent writer, which can produce surprising behavior even if hardware atomicity holds. Use language atomics to get defined semantics.

-

-

multi-word values or misaligned accesses → tearing possible

-

If the write spans multiple machine words (for example writing a 64-bit value on a 32-bit CPU, or a struct covering multiple words) or is misaligned, hardware can perform the write as multiple smaller writes. A concurrent reader may see a value composed of some bytes from the old value and some bytes from the new value — a torn value (part old, part new). That is not just “old or new.”

-

Example: on a 32-bit CPU writing a 64-bit integer might execute as two 32-bit stores; another core can read between them.

-

-

caches, store buffers, and visibility delays

-

Writing a value usually goes into the CPU core’s store buffer first; the write becomes globally visible when it propagates to other cores’ caches (through the coherence protocol). During that window another core may not yet see the new value and will read the old one. So a reader can see the old value for some time even after the write completed on the writer core.

-

The cache-coherence protocol (MESI / variants) guarantees eventual coherence, but not instantaneous visibility without synchronization/fences. On most coherent systems, once the write is visible it will appear as a single update for naturally aligned single-word writes; for multi-word/misaligned it may be torn.

-

-

compiler and CPU reorderings (visibility and sequencing)

-

Compilers can cache a value in a register, reorder memory operations, or eliminate reads/writes if the code is not marked atomic/volatile as required by the language semantics. That means the value you read might be a stale register value or the read might be optimized away.

-

CPUs reorder loads and stores (the allowed reorderings depend on the architecture). Without proper memory-ordering primitives (fences/atomic memory orders), the observed order of multiple memory operations can differ across threads.

-

-

language-level oddities (Java “out-of-thin-air”, C/C++ undefined)

-

In Java, unsynchronized data races allow a wide set of behaviors — theoretically even values that seem “out of thin air” in some relaxed executions (practical occurrences are rare and subtle).

volatileorAtomic*enforces ordering/visibility. -

In C/C++ a plain non-atomic concurrent write+read is a data race → undefined behavior. That means anything can happen (including program crash, or surprising compiler-generated assumptions that make behavior impossible to reason about).

-

Deadlock

-

Occurs when two or more threads are blocked forever, waiting on each other’s resources.

Lock-Free

-

When using locks, sections of the code that access shared memory are guarded by locks, allowing limited access to threads and blocking the execution of other threads.

-

In lock-free programming, the data itself is organized such that threads don't intervene much.

-

It can be done via segmenting the data between threads, and/or by using atomic operations.

Context Switching

-

The CPU switches between threads to provide concurrency.

-

Involves saving and loading thread states.

-

Has performance cost due to saving/restoring CPU registers, etc.

Parallelism

-

Executing multiple tasks simultaneously, typically on multiple cores or processors.

-

Focuses on true simultaneous execution .

-

Requires multiple physical or logical processing units.

-

Common in CPU-bound workloads (e.g., simulations, rendering).

-

Ex :

-

Using 4 cores to calculate physics updates for 4 game entities at the same time.

-

"Multiple workers doing different tasks at the same time ."

-

Concurrency

-

Managing multiple tasks at the same time, but not necessarily executing them simultaneously.

-

Focuses on interleaving execution of tasks.

-

Can occur on a single core .

-

Requires context switching.

-

Involves task coordination, scheduling, and synchronization.

-

Exs :

-

"One worker juggling multiple tasks — rapidly switching between them."

-

Switching between user input handling and background loading in a game loop.

-

-

About Multiplexer :

-

A multiplexer is a building block, not a full concurrency strategy.

-

Enables event-driven concurrency on a single thread, often forming the basis of asynchronous runtimes.

-

Common in network servers, GUIs, and I/O frameworks.

-

Sleeping

-

"odd thing: while sleeping for 0.8 ms in my main loop I get 15% cpu usage, but if I sleep for 1ms then the cpu usage drops to 1%".

-

This behavior is actually expected and reveals insights about how modern OSes handle thread scheduling and sleep durations:

-

Windows (and most OSes) have a default scheduler tick interval (usually 15.6ms or 1ms depending on system)

-

Below ~1ms, sleeps are often implemented as busy-waits (explaining your 15% CPU at 0.8ms)

-

Above 1ms, the OS can properly suspend the thread (hence 1% at 1ms)

-

-

The 1% vs 15% difference represents your CPU entering deeper sleep states

-

Wow, crazy.

-